Thursday, April 14, 2022

Elite imitation and flailing universities

Tuesday, January 18, 2022

Graduate students are people

Every scientist is a person. They have a unique personality and a unique life story. Their family, friends, education, hopes, romances, cultural background, past disappointments have shaped who they are today. This past has had a significant influence on their current motivation, fears, ability to work with others, confidence, sense of identity, and manner of communication. It is important that we grapple with all this complexity if we are to appreciate and respect others, and to help them be successful. Graduate students are not slaves, robots, or all the same. Graduate students are people.

These complexities are too often overlooked. But we must engage them if we are to personally care for students and colleagues, and relate to them in a manner that helps them be successful. These issues were brought home to me recently reading the novel, Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi. I thank my daughter for the gift, particularly as it was not the kind of book that I might normally have sought out.

The main character in the novel is Gifty, a graduate student in neuroscience at Stanford. Her parents immigrated to the U.S.A from Ghana and she grew up in Alabama, just like the author. Gifty's choice of research topic is motivated by her life experience including her brother's struggle with drug addiction. The research described in the novel is actually based on a real scientific paper written by a friend of the author.

Christina K. Kim, Li Ye, Joshua H. Jennings, Nandini Pichamoorthy, Daniel D. Tang, Ai-Chi W.Yoo, Charu Ramakrishnan, Karl Deisseroth

The novel gives an inside view of the life of a graduate student, describes experiments on mice, including the use of fluorescent proteins to image brain activity. Although science and graduate education is not the main point the novel, it may be good to give or recommend to non-scientists that you would like to understand a little of your world. The novel is easy to read and written in beautiful language. The main character (author) is an astute observer of herself, others, and social dynamics. The novel captures some of the intensity, independence, stubbornness, and introversion of a brilliant student.

The narrative naturally engages with a wide range of issues, including the immigrant experience and the associated prejudice, racism, poverty, dislocation, and alienation that are too often encountered. It considers family relationships, particularly the bond and tensions between a mother and an adult child. It gives a picture of what it may be like to be a young woman of colour in an elite institution. Then there is sexuality, white Pentecostal churches in the USA, science and religion, mental illness, drug addiction, a personal face on the opioid crisis, the philosophy of neuroscience, including the mind-brain problem,... This does seem like a long list of issues but the author manages to engage with them in a natural and meaningful way as part of a coherent narrative.

Perhaps the only criticism I might have is that I felt that the ending was a little too quick, neat, and may betray the complexity that the rest of the novel so beautifully captured.

Here are some other reviews and articles about the novel that I found most interesting. A review in the Washington post, A review in The New York Times, The back story of how a visit to a friends lab at Stanford led Gyasi to write the book.

Thursday, December 2, 2021

The tension between efficiency, innovation, and adaptability

If organisations are emergent can they be managed? This is the question I discussed in a previous post, stimulated by an article, The Dialogic Mindset: Leading Emergent Change in a Complex World by Gervase Bushe and Robert Marshak. They make the following claims.

To be sustainably successful, organizations have to manage learning as well as performing. This is one of the core paradoxes of management and organization theory: how to create organizations that can be simultaneously innovative and efficient; that is, how to best organize in order to learn and perform at the same time?

The most efficient forms of organizing, like assemblyline manufacturing, are also the least able to adapt and change. Our business models for succeeding in complex, uncertain environments, like popular music or pharmaceuticals, are highly inefficient and spend lots of money on innovation hoping for one monster hit to pay it all back. Learning and performing are paradoxically related because when someone is focused on performing well, they usually are not learning anything, and vice versa.

This tension is represented in the diagram below.

Money could come from cutting wasteful spending by the armed forces on jet fighters, which are not much use for guarding schools.

So the challenge for real leaders (not managers) is to foster an organisational culture that balances efficiency, adaptability, and innovation.

Monday, August 2, 2021

Chemical fingerprints on blood diamonds

“Fortunately, the majority of gentlemen who are persuaded to steal things don’t really know a huge amount about science”

This is a choice quote in a fascinating article, New Australian technology tracks down gold thieves and blood diamonds ["New tech to trace dodgy diamonds" in the print edition] in the Australian Financial Review (AFR) Weekend.

It describes the work of John Watling, Chief Scientist at the company Source Certain. Basically by measuring the relative amounts of different trace elements [chemical impurities] in a sample of gold or diamond one can determine what mine that it has come from.

Thursday, February 11, 2021

Desperately seeking tantalum

The road from materials research to commercial technology is a complex and tortuous one. It is not just a matter of what is physically possible. There are rigorous criteria that must be met along the way: financially competitive, mass production, reliability, durability, non-toxicity, ...

The materials needed don't just have to be available, cheap enough, and sufficiently abundant. One also needs supply chains that are not only reliable but also ethical.

In The Economist there is a fascinating (and disturbing) article that shows the complexities involved with the supply chains for just one of the metals used in our smart phones.

Why it’s hard for Congo’s coltan miners to abide by the lawTantalum, a metal used in smartphone and laptop batteries, is extracted from coltan ore. In 2019 40% of the world’s coltan was produced in the Democratic Republic of Congo, according to official data. More was sneaked into Rwanda and exported from there. Locals dig for the ore by hand in Congo’s eastern provinces, where more than 100 armed groups hide in the bush. Some mines are run by warlords who work with rogue members of the Congolese army to smuggle the coltan out.

Before reading this article I had no idea what coltan is and so I read the Wikipedia page.

On the science side, I wrongly guessed that coltan was some compound containing cobalt and tantalum. It is actually a mixture of two distinct crystals, tantalite [(Fe, Mn)Ta2O6] and columbite [(Fe, Mn)Nb2O6].

On the economic side, I found it interesting that until a few years ago Australia actually supplied most of the world's coltan.

In terms of political economy, this problem is an example of the "resource curse", a common experience of countries in The Bottom Billion.

If you are concerned about these issues and you live in Europe you might consider buying a Fairphone.

Friday, December 27, 2019

Question your intuitions and preconceptions

Perhaps, the bit that was most striking for me was the following.

What advice do you give to your talented undergraduates that differs from the advice your colleagues would give them?

I give almost all of them the advice to take some time off, in particular if they have any interest in development, which is generally the reason why they come to see me in the first place. But even if they don’t really, to spend a year or two in a developing country, working on a project. Not necessarily inner city. Any project spending time in the field.

It’s only through this exposure that you can learn how wrong most of your intuitions are and preconceptions are. I can tell it to them till they are blue in the face to not let themselves be guided by what seems obvious to them. But until they’ve confronted what they think is obvious to something entirely different, then it’s not clear.I think this relates to profound differences (cultural and economic and experiential) between rich countries and Majority World countries. Culture is what you assume is normal and unquestioned.

Saturday, November 2, 2019

Academic publishing in Majority World

Here are slides from a talk on the subject.

As always, it is important not to reinvent the wheel.

There are already some excellent resources and organisations.

A relevant organisation is AuthorAID which is related to inasp, and has online courses on writing. People I know who have taken these courses, or acted as mentors, speak highly of them.

Authors should also make use of software to correct English such as Grammarly.

Publishing Scientific Papers in the Developing World is a helpful book, stemming from a 2010 conference.

Erik Thulstrup has a nice chapter "How should a Young Researcher Write and Publish a Good Research Paper?"

Tuesday, August 20, 2019

The global massification of universities

The thing I found most surprising and interesting is the graphic below.

It compares the percentage of the population within 5 years of secondary school graduation are enrolled in higher education, in 2000 and 2017. In almost all parts of the world the percentage enrollment has doubled in just 17 years!

I knew there was rapid expansion in China and Africa, but did not realise it is such a global phenomenon.

Is this expansion good, bad, or neutral?

It is helpful to consider the iron triangle of access, cost, and quality. You cannot change one without changing at least one of the others.

I think that this expansion is based on parents, students, governments, and philanthropies holding the following implicit beliefs uncritically. Based on the history of universities until about the 1970s. Prior to that universities were fewer, smaller, more selective, had greater autonomy (both in governance, curriculum, and research).

1. Most students who graduated from elite institutions went on to successful/prosperous careers in business, government, education, ...

2. Research universities produced research that formed the foundation for amazing advances in technology and medicine, and gave profound new insights into the cosmos, from DNA to the Big Bang.

Caution: the first point does not imply that a university education was crucial to the graduates' success. Correlation and causality are not the same thing. The success of graduates may be just a matter of signaling. Elite institutions carefully selected highly gifted and motivated individuals who were destined for success. The university just certified that the graduates were ``hard-working, smart, and conformist.''

But the key point is these two observations (beliefs) concern the past and not the present. Universities are different. Massification and the stranglehold of neoliberalism (money, marketing, management, and metrics) mean that universities are fundamentally different, from the student experience to the nature of research.

According to Wikipedia,

Massification is a strategy that some luxury companies use in order to attain growth in the sales of product. Some luxury brands have taken and used the concept of massification to allow their brands to grow to accommodate a broader market.What do you think?

Are these the key assumptions?

Will massification and neoliberalism undermine them?

Tuesday, January 22, 2019

Post-colonial science

In the Western world issues such as these rightly get considerable attention. However, in the Majority World there is an issue that does considerable harm and is growing significantly. The basic claims are along the following lines. Modern science did not first arise in Europe but was already present in ancient cultures, often in religious texts. Post-colonial nations need to be proud of this heritage and this "science" should be an integral part of science education. Nations need to embrace their own methods and epistemologies consistent with their culture.

I recently become aware of just how prevalent these views are and the powerful political forces promoting them. You can get some of the flavour from this recent newspaper article and watching some of this video.

A relevant book is

Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science—from the Babylonians to the Maya

(Aside: The author, Dick Teresi wrote The God Particle with Leon Lederman.)

This book is authoritatively quoted in a recent book by a prominent South Asian political leader.

A helpful and critical review of Teresi's book is in Science. Basically, it is bad history. There is no doubt that various ancient civilisations did develop some pre-cursors of various aspects of modern mathematics, science, and technology. However, they were never comparable in scope, coherence, conceptual framework, and longevity to what happened in the "scientific revolution" in Europe. A very detailed debunk of some specific claims was given by Meera Nanda, and unfortunately received a vicious response.

So what is the source of the problem here?

I think several very distinct entities get conflated: colonialism, Western civilisation, science, technology, the greed and duplicity of some multinational corporations, and modernism.

A particularly tragic example of this conflation was arguably instrumental in the AIDS-HIV denialism of the South African government from 1999-2008. It was probably responsible for the death of hundreds of thousands of people.

Colonialism was a brutal system which ruthlessly exploited, humiliated, raped, and murdered millions of people across the globe. (See for example). Countless nations today labour under that horrific legacy. No doubt the colonising powers had a patronising view of the "natives", claiming they were bringing them the great achievements of Western civilisation such as science and modernism, and they ruthlessly used technology to maximise their exploitative agenda.

The subtle interplay between scientific, colonial, and theological ideas is described by Sarah Irving in

Natural Science and the Origins of the British Empire.

However, one can decry European colonialism but affirm good things about Western civilisation such as science.

One can decry how technology [based on science] is used to harm people but still affirm science.

Modernism is a particular world view or philosophical framework that claims scientific foundations. One can embrace science without embracing modernism.

I consider postcolonialism an understandable struggle for post-colonial nations to find an identity and direction in the era of globalisation. Somehow these nations need to honor the good parts of their own culture and history [including an accurate assessment of their scientific achievements], accept some good achievements of the West [science, democracy, rule of law, individual freedoms] without uncritically accepting dubious aspects of the West [consumerism, neoliberalism, narcissism, arrogance, ....].

Monday, November 26, 2018

A case for (and against) multi-dimensional measures

However, my problem is really one of abuse. I don't think metrics are totally meaningless or useless. Rather, it is the mindless use of metrics, with a disregard for their limitations, that is a problem.

This post is not about metrics, jobs, and funding. I have probably already written too many posts on that. Rather, I want to give two examples where I have found some multi-dimensional metrics helpful, when considering issues relating to public policy and development, particularly in the Majority World.

The case is that of the HDI (Human Development Index). Prior to its introduction people tended to use GDP (Gross Domestic Product) as a measure of how a country was performing and where it ranked in the world. In contrast, the HDI is a composite metric, factoring in income per capita, life expectancy, and education. The map below gives a sense of how the HDI varies around the world.

There is a lot one can learn from just the map. Sub-saharan Africa is the worst as a region. Even though India now has a middle class of several hundred million people, it is still comparable to some African countries.

Whenever I need to know something about a country, I look at the HDI. The fact that Australia often ranks in the top 3 tells me what a privileged environment I live in. Unfortunately, too many Australians really don't know or appreciate this.

I recently met a medical doctor from Niger [which I knew nothing about it]. He told me that Niger is ranked 182 out of 182 countries! This quickly gave me a sense of some of the challenges he faces.

Obviously, like any metric it has limitations. For example, some people prefer the IHDI (Inequality-adjusted HDI). The USA ranks 25th on the HDI.

The second example of a multi-dimensional metric concerns broader issues than human development, that is "human flourishing". This often means quite different things to different people. Last year there was a nice paper in PNAS that argues why this is important for both public policy, but also research in medicine and social sciences.

On the promotion of human flourishing

Tyler J. VanderWeele

The abstract gives an excellent summary.

Many empirical studies throughout the social and biomedical sciences focus only on very narrow outcomes such as income, or a single specific disease state, or a measure of positive effect. Human well-being or flourishing, however, consists in a much broader range of states and outcomes, certainly including mental and physical health, but also encompassing happiness and life satisfaction, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, and close social relationships. The empirical literature from longitudinal, experimental, and quasi-experimental studies is reviewed in an attempt to identify major determinants of human flourishing, broadly conceived. Measures of human flourishing are proposed. Discussion is given to the implications of a broader conception of human flourishing, and of the research reviewed, for policy, and for future research in the biomedical and social sciences.Broadly, when trying to describe and understand complex systems one should search for some measures of the properties of the system. Given the systems are complex one may need several measures. These will never be complete or perfect. But, provided one uses them with the appropriate caution this is a good thing.

Friday, September 14, 2018

Publishing for Majority World academics

Here are my slides.

As always, it is important not to reinvent the wheel.

There are already some excellent resources and organisations.

A particularly relevant organisation is AuthorAID which is related to inasp, and has an online course starting right now.

Publishing Scientific Papers in the Developing World is a helpful book, stemming from a 2010 conference.

Erik Thulstrup has a nice chapter "How should a Young Researcher Write and Publish a Good Research Paper?"

Sunday, February 11, 2018

Rethinking On-Line courses

Postscript (Feb. 13).

I forgot to link to this excellent NYT article.

Tuesday, November 7, 2017

Social qualities emerge from multiple interactions at multiple scales

Two big questions are:

How does a society make a transition between from a bad quality and a good quality?

What kind of initiatives can induce changes?

Initiatives can be individual or collective, political or economic, local or national, ...

For example, how does reduce corruption, which is endemic in many Majority world countries?

Or in the USA, why is public debate losing civility?

I think it is helpful to acknowledge the complexity of these issues. They have some similarity to wicked problems. They are problems that involve multiple interactions at multiple scales. Some of these interactions are competing and frustrated (in the spin glass sense!) and initiatives can lead to unintended consequences.

Whether you look at societies from a sociological, cultural, geographical, political, or economic perspective they involve multiple scales. For example, at the political level, one goes from local to city to state to national governments to the United Nations. In some countries corruption (bribes, extortion, nepotism, tax evasion,…) occurs at all levels. A policeman demands a bribe for a traffic violation. A university administrator changes records so his nephew, a mediocre student, can be admitted to medical school. The president of the country moves millions of dollars in foreign aid money into an off-shore bank account….

These phenonmena occur at multiple scales and involve multiple interactions. For example, an individual citizen will interact with many levels of government, and government agencies, and with each may be involved or impacted by a corrupt interaction.

Civility (respect, graciousness, politeness, listening) or uncivility (disrespect, rudeness, contempt, shouting) also occurs at many levels. These range from everyday conversations, comments on Facebook, to debate in parliament, to the Twitter feed of the President of the USA.

Michel Foucault, is one of the most influential (for better or worse) scholars in the humanities from the 20th century. He is particularly well known for his arguments that power operates at many levels and in many different ways in societies.

I find a multi-scale perspective helpful because it undercuts two extreme but common views concerning how we address significant social problems.

One view is the “top-down” perspective that if we just have the right national leader and the right laws a problem will be solved. This is argued for a whole range of issues ranging from corruption to sexual harassment, to “hate speech”.

The other extreme is the “bottom-up” view that the problem can be solved by individuals just making the right choices. Each individual should be polite to others and not give or take bribes. We need both approaches.

Moreover, I believe we need initiatives at all levels and interactions.

The importance of the absence of the intermediate scales (and the associated concept of social capital) was highlighted in Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, by the Harvard political scientist Robert D. Putnam.

An example of a multi-scale perspective is in the Oxfam book, From Poverty to Power: How active citizens and effective states can change the world.

A question that is both practically important and intellectually fascinating is:

What are the critical parameters and their values at which a society undergoes a “phase transition”?

Such a question is addressed in

The Epidemics of Corruption

Ph. Blanchard, A. Krueger, T. Krueger, P. Martin

The figure is from a paper, Small-World Networks of Corruption.

Thursday, October 5, 2017

Which single verb describes the mission of universities?

Research is all about thinking about the world we live in; whether it is genetics, cosmology, literature, engineering, or economics, ...

Reality is stratified and one observes different phenomena in different systems. As a result, one needs to think in distinct ways in order to develop concepts, laws, and methodologies for each stratum.

Note that thinking is central to experiments: thinking how to design the experiment and apparatus, and how to analyse the data produced and relate it to theory.

This is why we have disciplines. Each discipline involves a disciplined way of thinking.

Teaching is all about helping students learn how to think.

For specific disciplines, it involves learning how to think in a particular way.

Thinking like a condensed matter physicist is an art to learn.

Similarly, thinking like an economist is a unique way of thinking.

If this is the mission of modern universities are they successful?

On one level they have been incredibly successful.

Almost all the disciplines and knowledge we have were created in universities.

These ways of thinking have been incredibly productive and revealed things we might never have anticipated or dreamed of. Whether it is the genetic code, quantum field theory, game theory, or studies of ancient histories and cultures, ....

Furthermore, universities have really taught many students to think critically and creatively, not just about academic matters. University graduates have used their thinking skills in constructive ways, whether in inventions, starting companies, journalism, politics, philanthropy, ...

It should be acknowledged that this education does not just occur in the classroom but in informal contexts and involvement in student clubs and societies.

However, when you consider the resources that have been expended globally, both in teaching and research, you have to wonder whether universities are now failing at their mission.

This is reflected in a sparsity of critical thinking on many levels and in many contexts.

In the Majority World, universities try to mimic Western ones, at the superficial level of structures and curriculum. However, largely they focus on rote learning and not questioning teachers. This tragedy is captured with humour in my favourite Bollywood movie scene. Not only are students not taught how to think, they are actually taught not to think at all!

Yet, Elite universities now have a lot to answer for. The administration has become decoupled from the faculty and so we have metric madness and mindless marketing. Many of the statements or decision making processes (e.g. ignoring uncertainties, listing journal impact factors to 4 significant figures or cherry picking data to enhance the "ranking" of an institution) would be not be allowed in a freshman tutorial or lab.

Yet faculty are not without fault. Critical analysis will be avoided if publishing in a luxury journal is on the horizon. Then there is the hype of faculty about their latest research, whether in grant applications or public relations.

There are countless other ideas about what the mission of the university should be: training graduates for high paying jobs, wealth creation, enhancing national security, elite sports, industrial research, creating good citizens, ...

Many of these alternative missions are debatable, but regardless, they should be subordinate to the thinking mission.

Key to the thinking mission is academic freedom. Faculty and students need to be free to think what they want about what they want (within certain civil and resource constraints). Political interference and commercial interests inhibit such thinking.

It is interesting that Terry Eagleton, considers that the primary mission of universities is to critique society.

I thank Vinoth Ramachandra for teaching me this basic but crucial idea.

Friday, August 18, 2017

From instrumentation to climate change advocacy

The value of development of new instruments.

At Oxford Houghton was largely involved in finding new ways to use rocket based instruments measure the temperature and composition of the atmosphere at different heights. These were crucial for getting accurate data that revealed the extent of climate change and understanding climate dynamics. It was good for me to read this. As a theorist, I am often skeptical or at least unappreciative of the value of developing new instruments. I think it is partly because I have heard too many talks about instrument design where it really wasn't clear they were going to generate useful and reliable information, particularly that could be connected to theory.

A reluctant administrator.

I think the best people for senior management are those who don't want the job. The worst are those who desperately want the job. It is interesting to see that Houghton was quite reluctant to leave Oxford when he was asked to be director of Rutherford-Appleton Lab. Then he wanted to go back to Oxford but was persuaded to become head of the Meteorological Office. It is also refreshing to see how he pushed back against some of the "management" nonsense that people wanted to impose on the organisations that he led.

Rigorous peer review at the IPCC.

Just because something is peer reviewed does not mean it is true. However, when there is an overwhelming consensus about some issue in peer-reviewed literature, we can high confidence it is true. Furthermore, at the IPCC there was really a double layer of peer review. The reports were based on reviews of the peer-reviewed literature. Every sentence in the reports was debated and ultimately voted on by a committee of leading scientists with relevant expertise. It is very hard to get scientists to agree on anything. However, when they can agree it means there must be a high probability it is true.

Dirty tactics of denialists.

There are a few stories about the different antics of "observers" at IPCC meetings who worked tirelessly to get IPCC to dilute their reports and sow doubt. Unfortunately, Federick Seitz features along with the lawyer/lobbyist Don Pearlman, who worked for the Global Climate Coalition.

Gracious public engagement.

The book describes how Houghton has worked hard to engage with climate change denialists, particularly among Conservative Christian leaders in the USA.

Finally, the book makes a strong case for concerted action on climate change. The most striking figure in the book was the map of Bangladesh showing how much will go under water, with just a one-metre rise in sea level. As often the case it is the poor that suffer the most.

Saturday, August 5, 2017

Who was the greatest theoretical chemist of the 19th century?

He even successfully predicted the existence of new elements and their properties.

A friend who is a high school teacher [but not a scientist] asked me about how he should teach the periodic table to chemistry students. It is something that students often memorise, especially in rote-learning cultures, but have little idea about what it means and represents. It makes logical sense, even without quantum mechanics. This video nicely captures both how brilliant Mendeleev was and the logic behind the table.

A key idea is how each column contains elements with similar chemical and physical properties and that as one goes down the column there are systematic trends.

It is good for students to see this with their own eyes.

This video from the Royal Society of Chemistry shows in spectacular fashion how the alkali metals are all highly reactive and that as one goes down the column the reactivity increases.

The next amazing part of the story is how once quantum theory came along it all started to make sense!

Monday, June 19, 2017

The scientific relevance of your hobby

However, scientific discoveries, particularly big ones, often involve creativity, serendipity, or thinking outside the box.

I noticed two examples of this recently.

The first was how fascination with a cheap child's toy led to the key idea behind the development of extremely cheap centrifuge [paperfuge] for health diagnostics in the Majority World.

The second example was a New York Times article about a recent paper that argues that key to Pasteur's discovery of molecular chirality was his interest in art.

Another example, is Harry Kroto who shared The Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of buckyballs. He credited playing with Meccano as a child as very important in his scientific development.

Can you think of other examples?

Tuesday, June 13, 2017

How might we teach students to actually think?

1. To think.

2. To think like a physicist.

3. To think like a condensed matter physicist.

4. The specific technical content of the course.

The last one is arguably easier than the others.

I also think it is the least important. Others will disagree.

We don't reflect enough on how we might achieve the other goals.

The biggest challenge of improving education in the Majority World is not lack of material resources but changing the culture of rote learning and teaching critical thinking.

[This is highlighted in a NYTimes piece about China and a very funny video about India ITs].

Last week the UQ School of Maths and Physics Teaching Seminar was given by Peter Ellerton who works for the UQ Critical Thinking project.

The slides from a similar talk are here.

In the talk he mostly walked us through the three graphics shown here.

[If you click on the image you can see a high resolution .pdf]

The main value of all this is it puts names, categories, and questions on what I want to do. I found the third graphic the most helpful because it has some very specific questions we can ask students to get them to reflect more on what they are learning and in the process learn to think more critically.

Wednesday, March 8, 2017

Is complexity theory relevant to poverty alleviation programs?

Recently, there has been a surge of interest among development policy analysts about how complexity theory may be relevant in poverty alleviation programs.

On an Oxfam blog there is a helpful review of three books on complexity theory and development.

I recently read some of one of these books, Aid on the Edge of Chaos: Rethinking International Cooperation in a Complex World, by Ben Ramalingham.

Here is some of the publisher blurb.

Ben Ramalingam shows that the linear, mechanistic models and assumptions on which foreign aid is built would be more at home in early twentieth century factory floors than in the dynamic, complex world we face today. All around us, we can see the costs and limitations of dealing with economies and societies as if they are analogous to machines. The reality is that such social systems have far more in common with ecosystems: they are complex, dynamic, diverse and unpredictable.

Many thinkers and practitioners in science, economics, business, and public policy have started to embrace more 'ecologically literate' approaches to guide both thinking and action, informed by ideas from the 'new science' of complex adaptive systems. Inspired by these efforts, there is an emerging network of aid practitioners, researchers, and policy makers who are experimenting with complexity-informed responses to development and humanitarian challenges.

This book showcases the insights, experiences, and often remarkable results from these efforts. From transforming approaches to child malnutrition, to rethinking processes of economic growth, from building peace to combating desertification, from rural Vietnam to urban Kenya, Aid on the Edge of Chaos shows how embracing the ideas of complex systems thinking can help make foreign aid more relevant, more appropriate, more innovative, and more catalytic. Ramalingam argues that taking on these ideas will be a vital part of the transformation of aid, from a post-WW2 mechanism of resource transfer, to a truly innovative and dynamic form of global cooperation fit for the twenty-first century.The first few chapters give a robust and somewhat depressing critique of the current system of international aid. He then discusses complexity theory and finally specific case studies.

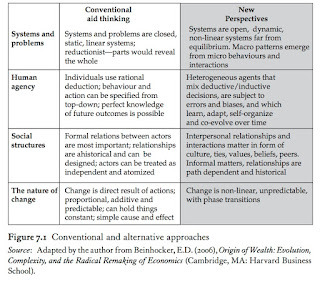

The Table below nicely contrasts two approaches.

A friend who works for a large aid NGO told me about the book and described a workshop (based on the book) that he attended where the participants even used modeling software.

I have mixed feelings about all of this.

Any problem in society involves a complex system (i.e. many interacting components). Insights, both qualitative and quantitative, can be gained from "physics" type models. Examples I have posted about before, include the statistical mechanics of money and the universality in probability distributions for certain social quantities.

Simplistic mechanical thinking, such as that associated with Robert McNamara in Vietnam and then at the World Bank, is problematic and needs to be critiqued. Even a problem as 'simple" as replacing wood burning stoves turns out to be much more difficult and complicated than anticipated.

A concrete example discussed in the book is that of positive deviance, which takes its partial motivation from power laws.

Here are some concerns.

Complexity theory suffers from being oversold. It certainly gives important qualitative insights and concrete examples in "simple" models. However, to what extent complexity theory can give a quantitative description of real systems is debatable. This is particularly true of the idea of "the edge of chaos" that features in the title of the book. A less controversial title would have replaced this with simply "emergence", since that is a lot of what the book is really about.

Some of the important conclusions of the book could be arrived at by different more conventional routes. For example, a major point is that "top down" approaches are problematic. This is where some wealthy Westerners define a problem, define the solution, then provide the resources (money, materials, and personnel) and impose the solution on local poor communities. A more "bottom up" or "complex adaptive systems" approach is where one consults with the community, gets them to define the problem and brainstorm possible solutions, give them ownership of implementing the project, and adapt the strategy in response to trials. One can come to this same approach if ones starting point is simply humility and respect for the dignity of others. We don't need complexity theory for that.

The author makes much of the story of Sugata Mitra, whose TED talk, "Kids can teach themselves" has more than a million views. He puts some computer terminals in a slum in India and claims that poor uneducated kids taught themselves all sorts of things, illustrating "emergent" and "bottom up" solutions. It is a great story. However, it has received some serious criticism, which is not acknowledged by the author.

Nevertheless, I recommend the book and think it is a valuable and original contribution about a very important issue.

Thursday, December 22, 2016

Are power laws good for anything?

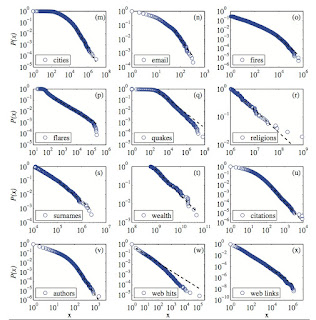

A critical review is here, which contains the figure below.

Complexity theory makes much of these power laws.

But, sometimes I wonder what the power laws really tell us, and particularly whether for social and economic issues they are good for anything.

Recently, I learnt of a fascinating case. Admittedly, it does not rely on the exact mathematical details (e.g. the value of the power law exponent!).

The case is described in an article by Dudley Herschbach,

Understanding the outstanding: Zipf's law and positive deviance

and in the book Aid at the Edge of Chaos, by Ben Ramalingam.

Here is the basic idea. Suppose that you have a system of many weakly interacting (random) components. Based on the central limit theorem one would expect that a particular random variable would obey a normal (Gaussian) distribution. This means that large deviations from the mean are extremely unlikely. However, now suppose that the system is "complex" and the components are strongly interacting. Then the probability distribution of the variable may obey a power law. In particular, this means that large deviations from the mean can have a probability that is orders of magnitude larger than they would be if the distribution was "normal".

Now, lets make this concrete. Suppose one goes to a poor country and looks at the weight of young children. One will find that the average weight is significantly smaller than in an affluent country, and most importantly the average less than is healthy for brain and physical development. These low weights arise from a complex range of factors related to poverty: limited money to buy food, lack of diversity of diet, ignorance about healthy diet and nutrition, famines, giving more food to working members of the family, ...

However, if the weights of children obeys a power law, rather than a normal, distribution one might be hopeful that one could find some children who have a healthy weight and investigate what factors contribute to that. This leads to the following.

Positive Deviance (PD) is based on the observation that in every community there are certain individuals or groups (the positive deviants), whose uncommon but successful behaviors or strategies enable them to find better solutions to a problem than their peers. These individuals or groups have access to exactly the same resources and face the same challenges and obstacles as their peers.

The PD approach is a strength-based, problem-solving approach for behavior and social change. The approach enables the community to discover existing solutions to complex problems within the community.

The PD approach thus differs from traditional "needs based" or problem-solving approaches in that it does not focus primarily on identification of needs and the external inputs necessary to meet those needs or solve problems. A unique process invites the community to identify and optimize existing, sustainable solutions from within the community, which speeds up innovation.

The PD approach has been used to address issues as diverse as childhood malnutrition, neo-natal mortality, girl trafficking, school drop-out, female genital cutting (FGC), hospital acquired infections (HAI) and HIV/AIDS.

The role of superconductivity in development of the Standard Model

In 1986, Steven Weinberg published an article, Superconductivity for Particular Theorists , in which he stated "No one did more than N...

-

Is it something to do with breakdown of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation? In molecular spectroscopy you occasionally hear this term thro...

-

Nitrogen fluoride (NF) seems like a very simple molecule and you would think it would very well understood, particularly as it is small enou...

-

I welcome discussion on this point. I don't think it is as sensitive or as important a topic as the author order on papers. With rega...