For a diverse range of chemical compounds, the strength of hydrogen bonds [parametrised by the binding energy and/or bond length] is correlated with a wide range of physical properties such as bond lengths, vibrational frequencies and intensities, and isotope effects. I have posted about many of these and a summary of the main ones is in this paper.

One correlation which is particularly important for practical reasons is the correlation of bond strength (and length) with the chemical shift associated with proton NMR.

The chemical shift is the difference between the NMR resonant frequency of the proton in a specific molecule and that of a free proton. The first important point is that although this shift is extremely small (typically one part in 100,000!) one can measure it extremely accurately.

More importantly, this shift is quite sensitive to the local chemical bonding and so one can use it to actually identify the bonding in unknown molecules (e.g. protein structure determination).

Indeed, if you go to the library and open up a book on NMR or organic chemistry you will find tables and figures giving the chemical shifts associated with different functional groups.

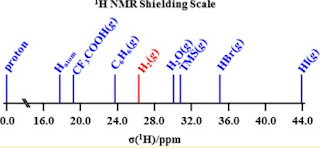

The figure below (taken from here) shows proton chemical shifts for some different molecules.

Why does this happen?

Very roughly the chemical shift is largely determined by the local electronic charge density near the proton and this is modified by the local chemical bonding.

What about hydrogen bonds?

The figure below shows the correlation between the chemical shift and the donor-acceptor distance R for a range of molecules, as found in a 1980 paper.

Confusing aside: the figure shows the chemical shift relative to the standard TMS and so involves negative values.

Why does this matter?

The correlation provides a means to accurately "measure" the donor-acceptor bond length when one does not have direct measurements (e.g. by X-ray diffraction). This is particularly useful in proteins. Indeed, some of the first claims in 1994 on the controversial topic of low-barrier H-bonds (i.e. strong H-bonds) in enzymes were largely based on the observation of unusually small chemical shifts. Some of the subtle issues are discussed here. Another signature is the isotopic fractionation factor.

Although one can calculate these chemical shifts with "black box" computational chemistry, using formulae originally derived by Ramsey in 1950, understanding the underlying physics of the correlations is not clear.

I thank my student Anna Symes for helpful discussions about this topic.

Monday, October 31, 2016

Thursday, October 27, 2016

Emergent quantum matter and topology

Today I am giving a talk at IISER Kolkata. My host Chiranjib Mitra requested that I include some discussion of this year's Nobel Prize in Physics. This was very helpful as I think the talk now flows better and there are more illustrations of my main points. But, there is less time to talk about my own work...

Here is the current version of the slides. I welcome comments.

Here is the current version of the slides. I welcome comments.

Tuesday, October 25, 2016

A nice demonstration of classical chiral symmetry breaking

I like concrete classroom demonstrations.

Andrew Boothroyd recently showed me a very elegant demonstration based on this paper

Spontaneous Chirality in Simple Systems

Galen T. Pickett, Mark Gross, and Hiroko Okuyama

It considers hard spheres confined to a cylinder. Different phases depending on the value of D, the ratio of the diameters of the cylinder and the spheres. The phase diagram is below.

Andrew has a nice demonstration using ping pong balls and a special transparent plastic cylinder that has the right diameter to produce a chiral phase. He shows it during a colloquium and sometimes even gets an applause!

I found a .ppt that has the nice pictures below.

Andrew Boothroyd recently showed me a very elegant demonstration based on this paper

Spontaneous Chirality in Simple Systems

Galen T. Pickett, Mark Gross, and Hiroko Okuyama

It considers hard spheres confined to a cylinder. Different phases depending on the value of D, the ratio of the diameters of the cylinder and the spheres. The phase diagram is below.

I found a .ppt that has the nice pictures below.

Wednesday, October 19, 2016

How to give a bad science talk

Amongst his one page guides John Wilkins [my postdoc supervisor] has

Guidelines for giving a truly terrible talk

I am not sure if it is funny or just plain painful. But it does drive home the points.

All students (and some faculty) should be forced to watch it in full.

Guidelines for giving a truly terrible talk

"Strict adherence to the following time-tested guidelines will ensure that both you and your work remain obscure and will guarantee an audience of minimum size at your next talk."Independently, David Sholl has illustrated the problems in concrete ways with an actual talk "The Secrets of Memorably Bad Presentations"

I am not sure if it is funny or just plain painful. But it does drive home the points.

All students (and some faculty) should be forced to watch it in full.

Friday, October 14, 2016

Recommendations needed on software to correct English grammar

A necessary ingredient to surviving and possibly prospering in science is the ability to write clearly in English. Yet many students are not native English speakers and some have had poor education and training. For some, it is even difficult to write basic sentences without grammar and spelling mistakes.

This is a serious issue for both students and advisors.

Unfortunately, what happens too often is that advisors spend too much time correcting the English in drafts of papers and thesis chapters rather than focusing on the scientific content.

Even, worse lazy or over-committed advisors don't do the corrections and referees, examiners, or editors are left with the problem.

Advisors, co-authors, and examiners can get quite irritated in the process.

Students need to realise they are really hurting themselves in not addressing this issue.

Is there a solution?

I try to encourage students and postdocs to pair up and read each other's drafts. However, this is not really quid pro quo (i.e. a fair transaction) if one is a much stronger English writer than another.

A colleague recently told me about a solution he found worked very well. His institution bought the Grammarly software for a graduate student, who was excellent in science but poor in English. Before giving any document to the advisor the student had to run it through the software. This not only finds spelling and grammatical errors but suggests alternatives and gives the reasons for the error.

Thus, it not only corrects the errors but trains the students. It does work. The student can now write better even without the software.

There is a free version of the software that has limited capability. The premium version costs US$140 per year. You can buy just 3 months for US$60.

I downloaded the free version to test it. It found a few minor mistakes in this blog post! I also tested it on a student essay and a weekly report. It found some errors, missed a few, and pointed out that there were several errors that could be corrected with the premium version (very clever marketing!).

Does anyone else have experience with this software, either themselves or getting their students or postdocs to use it?

Unless they are at a poor institution in the Majority world I think faculty need to bite tell students they need to buy the software.

If students are serious about getting a Ph.D with less stress and keeping their advisor on good terms they should buy it.

In the grander scheme of things this is a small amount of money.

I welcome recomnendations on alternatives.

On the lighter side do a Google image search on "funny English signs"

This is a serious issue for both students and advisors.

Unfortunately, what happens too often is that advisors spend too much time correcting the English in drafts of papers and thesis chapters rather than focusing on the scientific content.

Even, worse lazy or over-committed advisors don't do the corrections and referees, examiners, or editors are left with the problem.

Advisors, co-authors, and examiners can get quite irritated in the process.

Students need to realise they are really hurting themselves in not addressing this issue.

Is there a solution?

I try to encourage students and postdocs to pair up and read each other's drafts. However, this is not really quid pro quo (i.e. a fair transaction) if one is a much stronger English writer than another.

A colleague recently told me about a solution he found worked very well. His institution bought the Grammarly software for a graduate student, who was excellent in science but poor in English. Before giving any document to the advisor the student had to run it through the software. This not only finds spelling and grammatical errors but suggests alternatives and gives the reasons for the error.

Thus, it not only corrects the errors but trains the students. It does work. The student can now write better even without the software.

There is a free version of the software that has limited capability. The premium version costs US$140 per year. You can buy just 3 months for US$60.

I downloaded the free version to test it. It found a few minor mistakes in this blog post! I also tested it on a student essay and a weekly report. It found some errors, missed a few, and pointed out that there were several errors that could be corrected with the premium version (very clever marketing!).

Does anyone else have experience with this software, either themselves or getting their students or postdocs to use it?

Unless they are at a poor institution in the Majority world I think faculty need to bite tell students they need to buy the software.

If students are serious about getting a Ph.D with less stress and keeping their advisor on good terms they should buy it.

In the grander scheme of things this is a small amount of money.

I welcome recomnendations on alternatives.

On the lighter side do a Google image search on "funny English signs"

Wednesday, October 12, 2016

A quantum dimension to the Kosterlitz-Thouless transition

In my previous post about the 2016 Nobel Prize in Physics I stated that the Kosterlitz-Thouless transition was a classical phase transition (involving topological objects = vortices), in contrast to the quantum phase transitions associated with topological phases of matter.

However, on reflection I realised that it should not be overlooked that there is something distinctly quantum about the KT transition. In a two-dimensional superfluid it involves the binding of pairs of vortices and anti-vortices. These each have a quantum of circulation (+/-h/m where h is Planck's constant and m is the particle mass).

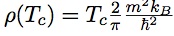

At the KT transition temperature Tc there is a finite jump in the superfluid density rho. The value just below Tc is related to Tc by

Note that Planck's constant appears in this equation.

In a classical world (h=0), Tc would be zero and there would be no KT transition!

This universal relation was derived by Nelson and Kosterlitz in 1977

The figure below contains a range of experimental data testing this relation.

Friday, October 7, 2016

Faculty job candidates need to know and articulate the big picture

Are there any necessary or sufficient conditions for getting a faculty position?

Previously, I suggested that a key element is actually dumb luck: being in the right place at the right time. But that is not my focus here.

Twenty years ago when I was struggling to find a faculty job the mythology was that you had to have at least two PRLs and get an invited talk at an APS March Meeting. And doing a postdoc at certain places (e.g. ITP Santa Barbara) would help...

Now the mythology seems to be that you need to have Nature and Science papers....

But, this in actually not the case.

This is not a sufficient condition.

Search committees want to hire someone who can lead an independent research program and can move into new areas.

Several department chairs have said things to me along the lines of "It is amazing how we interview some candidates who have impressive publication lists involving papers in luxury journals but when we actually talk to them we quickly lose interest. We find they lack any sort of big picture. Some cannot even articulate why their own papers are scientifically important, let alone future directions. It seems they have been a student or postdoc in some big group and they have developed some narrow (but important) technical expertise (e.g. device fabrication, running computational chemistry codes, using an STM, ...) that is indispensable to the group."

I find this quite sad. It is sad for the individuals. All the hard work in the hope of getting a faculty position will have gone to waste. I also find it sad when faculty don't prioritise training group members.

How can you stop this being you?

Read papers, including outside your actual research project.

Talk to people in different research groups about what they and you are doing.

Go to seminars, even when you are busy.

But, particularly write papers yourself.

If you are the first author you really should write the first draft, including the introduction yourself. Don't let your boss (or someone more experienced) do it or expect them to.

Your draft may be poor and get heavily edited or even discarded completely. But you will learn from the process and with time confidence and competence will follow.

Previously, I suggested that a key element is actually dumb luck: being in the right place at the right time. But that is not my focus here.

Twenty years ago when I was struggling to find a faculty job the mythology was that you had to have at least two PRLs and get an invited talk at an APS March Meeting. And doing a postdoc at certain places (e.g. ITP Santa Barbara) would help...

Now the mythology seems to be that you need to have Nature and Science papers....

But, this in actually not the case.

This is not a sufficient condition.

Search committees want to hire someone who can lead an independent research program and can move into new areas.

Several department chairs have said things to me along the lines of "It is amazing how we interview some candidates who have impressive publication lists involving papers in luxury journals but when we actually talk to them we quickly lose interest. We find they lack any sort of big picture. Some cannot even articulate why their own papers are scientifically important, let alone future directions. It seems they have been a student or postdoc in some big group and they have developed some narrow (but important) technical expertise (e.g. device fabrication, running computational chemistry codes, using an STM, ...) that is indispensable to the group."

I find this quite sad. It is sad for the individuals. All the hard work in the hope of getting a faculty position will have gone to waste. I also find it sad when faculty don't prioritise training group members.

How can you stop this being you?

Read papers, including outside your actual research project.

Talk to people in different research groups about what they and you are doing.

Go to seminars, even when you are busy.

But, particularly write papers yourself.

If you are the first author you really should write the first draft, including the introduction yourself. Don't let your boss (or someone more experienced) do it or expect them to.

Your draft may be poor and get heavily edited or even discarded completely. But you will learn from the process and with time confidence and competence will follow.

Wednesday, October 5, 2016

2016 Nobel Prize in Physics: Topology matters in condensed matter

I was delighted to see this year's Nobel Prize in Physics awarded to Thouless, Haldane, and Kosterlitz

”for theoretical discoveries of topological phase transitions and topological phases of matter”.

A few years ago I predicted Thouless and Haldane, but was not sure they would ever get it. I am particularly glad they were not bypassed, but rather pushed forward, by topological insulators.

There is a very nice review of the scientific history on the Nobel site.

Here are a few random observations, roughly in order of decreasing importance.

First, it is important to appreciate that there are two distinct scientific discoveries here. They do both involve Thouless and topology, but they really are distinct and so Thouless’ contribution in both is all the more impressive.

The “topological phase transition” concerns the Kosterlitz-Thouless transition which is a classical phase transition (i.e. driven by thermal fluctuations) which is driven by vortices (topological objects,

which can also be viewed as non-linear excitations).

The KT transition and the low temperature phase is remarkably different from other phase transitions and phases of matter. It is a truly continuous transition in that all the derivatives of the free energy are continuous and a Taylor expansion about the critical temperature is not defined.

Yet the superfluid density undergoes a jump at the KT transition temperature.

The low temperature phase has power law correlations with an exponent which is not only irrational but non-universal (i.e. it depends on the coupling constant and temperature).

There are deep connections to quantum phase transitions in one-dimensional systems, e.g. in a spin-1/2 XXZ spin chain, but that is another story.

Topological states of matter are strictly quantum.

Having done the KT transition there is no reason why Thouless would have been led to the formulation of the quantum Hall effect in terms of topological invariants.

That is really an independent discovery. Furthermore, the topology and maths is much more abstract because it is not in real space but involves fibre bundles, Chern numbers, and Berry connections.

All of this phenomena are striking examples of emergence in physics: surprising new phenomena, entities, and concepts.

But, here there is a profound issue about theory preceding experiment.

Almost always emergent phenomena are discovered experimentally and later theory scrambles to explain what is going on.

But, here it seems to be different. KT was predicted and then observed.

The Haldane phase was predicted and then observed in real materials.

When I give my emergent quantum matter talk, I sometimes say: “I can’t think of an example of where a new quantum state of matter was predicted and then observed. Sometimes people give the example of BEC in ultracold atomic gases and of topological insulators but they are essentially non-interacting systems."

On the other hand, it is important to acknowledge that all of this was done with effective Hamiltonians (XY models and Heisenberg spin chains). No one started with a specific material (chemical composition) and then predicted what quantum state it would have without any input from experiment.

The background article helped me better appreciate the unique contributions of Kosterlitz. I was in error not to suggest him before. By himself he worked out the renormalisation group (RG) equations for the transition. Also with Nelson he predicted the universal jump in the superfluid density.

As an aside, it is fascinating that the same RG equations appear in the anisotropic Kondo model and were discovered earlier by Phil Anderson, which was also before Wilson did RG.

The background article also notes how it took a while for Haldane’s 1983 conjecture (that integer spin chains had an energy gap to the lowest excited triplet state) to be accepted, and suggests experiment decided. It should be pointed out that on the theory side that the numerics was not clear (see e.g., this 1989 review by Ian Affleck) until Steve White developed the DMRG (Density Matrix Renormalisation Group) for one-dimensional quantum many-body systems and laid the matter to rest in 1994 by calculating the energy gap and correlation length to five significant figures!

Later I have some minor sociology comments, but don’t want to spoil all the lovely science in this post.

”for theoretical discoveries of topological phase transitions and topological phases of matter”.

A few years ago I predicted Thouless and Haldane, but was not sure they would ever get it. I am particularly glad they were not bypassed, but rather pushed forward, by topological insulators.

There is a very nice review of the scientific history on the Nobel site.

Here are a few random observations, roughly in order of decreasing importance.

First, it is important to appreciate that there are two distinct scientific discoveries here. They do both involve Thouless and topology, but they really are distinct and so Thouless’ contribution in both is all the more impressive.

The “topological phase transition” concerns the Kosterlitz-Thouless transition which is a classical phase transition (i.e. driven by thermal fluctuations) which is driven by vortices (topological objects,

which can also be viewed as non-linear excitations).

The KT transition and the low temperature phase is remarkably different from other phase transitions and phases of matter. It is a truly continuous transition in that all the derivatives of the free energy are continuous and a Taylor expansion about the critical temperature is not defined.

Yet the superfluid density undergoes a jump at the KT transition temperature.

The low temperature phase has power law correlations with an exponent which is not only irrational but non-universal (i.e. it depends on the coupling constant and temperature).

There are deep connections to quantum phase transitions in one-dimensional systems, e.g. in a spin-1/2 XXZ spin chain, but that is another story.

Topological states of matter are strictly quantum.

Having done the KT transition there is no reason why Thouless would have been led to the formulation of the quantum Hall effect in terms of topological invariants.

That is really an independent discovery. Furthermore, the topology and maths is much more abstract because it is not in real space but involves fibre bundles, Chern numbers, and Berry connections.

All of this phenomena are striking examples of emergence in physics: surprising new phenomena, entities, and concepts.

But, here there is a profound issue about theory preceding experiment.

Almost always emergent phenomena are discovered experimentally and later theory scrambles to explain what is going on.

But, here it seems to be different. KT was predicted and then observed.

The Haldane phase was predicted and then observed in real materials.

When I give my emergent quantum matter talk, I sometimes say: “I can’t think of an example of where a new quantum state of matter was predicted and then observed. Sometimes people give the example of BEC in ultracold atomic gases and of topological insulators but they are essentially non-interacting systems."

On the other hand, it is important to acknowledge that all of this was done with effective Hamiltonians (XY models and Heisenberg spin chains). No one started with a specific material (chemical composition) and then predicted what quantum state it would have without any input from experiment.

The background article helped me better appreciate the unique contributions of Kosterlitz. I was in error not to suggest him before. By himself he worked out the renormalisation group (RG) equations for the transition. Also with Nelson he predicted the universal jump in the superfluid density.

As an aside, it is fascinating that the same RG equations appear in the anisotropic Kondo model and were discovered earlier by Phil Anderson, which was also before Wilson did RG.

The background article also notes how it took a while for Haldane’s 1983 conjecture (that integer spin chains had an energy gap to the lowest excited triplet state) to be accepted, and suggests experiment decided. It should be pointed out that on the theory side that the numerics was not clear (see e.g., this 1989 review by Ian Affleck) until Steve White developed the DMRG (Density Matrix Renormalisation Group) for one-dimensional quantum many-body systems and laid the matter to rest in 1994 by calculating the energy gap and correlation length to five significant figures!

Later I have some minor sociology comments, but don’t want to spoil all the lovely science in this post.

Monday, October 3, 2016

A critical review of holographic claims about condensed matter

There is a very helpful review article

Demystifying the Holographic Mystique by Dmitri Khveshchenko

In order to motivate a proper full reading I just give a few choice quotes.

Demystifying the Holographic Mystique by Dmitri Khveshchenko

In order to motivate a proper full reading I just give a few choice quotes.

Thus far, however, a flurry of the traditionally detailed (hence, rarely concise) publications on the topic have generated not only a good deal of enthusiasm but some reservations as well. Indeed, the proposed ’ad hoc’ generalizations of the original string-theoretical construction involve some of its most radical alterations, whereby most of its stringent constraints would have been aban- doned in the hope of still capturing some key aspects of the underlying correspondence. This is because the target (condensed matter) systems generically tend to be neither conformally, nor Lorentz (or even translationally and/or rotationally) invariant and lack any supersymmetric (or even an ordinary) gauge symmetry with some (let alone, large) rank-N non-abelian group.

Moreover, while sporting a truly impressive level of technical profess, the exploratory ’bottom-up’ holographic studies have not yet helped to resolve such crucially important issues as:

• Are the conditions of a large N, (super)gauge sym- metry, Lorentz/translational/rotational invariance of the boundary (quantum) theory indeed necessary for establishing a holographic correspondence with some weakly coupled (classical) gravity in the bulk?

• Are all the strongly correlated systems (or only a precious few) supposed to have gravity duals?

• What are the gravity duals of the already documented NFLs?

• Given all the differences between the typical condensed matter and string theory problems, what (other than the lack of a better alternative) justifies the adaptation ’ad verbatim’ of the original (string-theoretical) holographic ’dictionary’?

and, most importantly:

• If the broadly defined holographic conjecture is indeed valid, then why is it so?

Considering that by now the field of CMT holography has grown almost a decade old, it would seem that answering such outstanding questions should have been considered more important than continuing to apply the formal holographic recipes to an ever increasing number of model geometries and then seeking some resemblance to the real world systems without a good understanding as to why it would have to be there in the first place. In contrast, the overly pragmatic ’shut up and calculate’ approach prioritizes computational tractability over phys- ical relevance, thus making it more about the method (which readily provides a plethora of answers but may struggle to specify the pertinent questions) itself, rather than the underlying physics.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

What Americans might want to know about getting a job in an Australian university

Universities and scientific research in the USA are facing a dire future. Understandably, some scientists are considering leaving the USA. I...

-

Is it something to do with breakdown of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation? In molecular spectroscopy you occasionally hear this term thro...

-

Nitrogen fluoride (NF) seems like a very simple molecule and you would think it would very well understood, particularly as it is small enou...

-

I welcome discussion on this point. I don't think it is as sensitive or as important a topic as the author order on papers. With rega...