This is a common narrative. But is it actually true?

Late last year, The Economist had an interesting article "The Creed of Speed: Is business really getting quicker?"

They look at certain objective quantitative measures to argue that the (surprising) answer to the question is no.

It is worth reading the whole article, but here a few snippets.

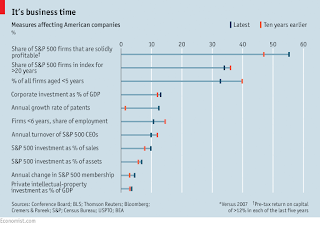

The graph below shows how little some measures have changed in the past 10 years.

More creative destruction would seem to imply that firms are being created and destroyed at a greater rate. But the odds of a company dropping out of the S and P 500 index of big firms in any given year are about one in 20—as they have been, on average, for 50 years. About half of these exits are through takeovers. For the economy as a whole the rates at which new firms are born are near their lowest since records began, with about 8% of firms less than a year old, compared with 13% three decades ago. Youngish firms, aged five years or less, are less important measured by their number and share of employment.I love the line:

People who use dating apps still go to restaurants.So there is a puzzle: people feel things are changing rapidly but they actually are not.

A better explanation of the puzzle comes from looking more closely at the effect of information flows on businesses. There is no doubt that there are far more data coursing round firms than there were just a few years ago. And when you are used to information accumulating in a steady trickle, a sudden flood can feel like a neck-snapping acceleration. Even though the processes about which you know more are not inherently moving faster, seeing them in far greater detail makes it feel as if time is speeding up.I think that there is another reason why the perception of change is greater than the reality: the existence of a whole industry of consultants and managers whose (highly prosperous) livelihood depends on "change management". They spend a lot of time, energy, and money selling the "rapid change" and "impending crisis" line.

The article concludes by emphasising the importance of long term investments, particularly by large firms.

New technologies spread faster than ever, says Andy Bryant, the chairman of Intel; shares in the company change hands every eight months. But to keep up with Moore’s Law the firm has to have long investment horizons. It puts $20 billion a year into plant and R and D. “Our scientists have a ten-year view…If you don’t take a long view it is hard to keep your production costs consistent with Moore’s Law.”

And what about Apple, with the frantic antics of which this article began? Its directors have served for an average of six years. It has invested heavily in fixed assets, such as data centres, which will last for over a decade. It has pursued truly long-term strategies such as acquiring the capacity to design its own chips. Mr Cook has been in his post for four years and slogged away at the firm for 14 years before that. Apple is 39 years old, and it has issued bonds that mature in the 2040s.

Forget frantic acceleration. Mastering the clock of business is about choosing when to be fast and when to be slow.Now what about universities, particularly large ones with good reputations?

First, they are changing much more slowly than companies and much less susceptible to "market" pressures.

John Quiggin did a comparative study, entitled Rank delusions, of the list of leading US companies and leading universities over the last 100 years. In contrast, to the companies the university rankings are virtually unchanged.

Second, if you consider institutions such as Harvard, Oxford, Georgia Tech, Ohio State, Indian Institutes of Technology, University of Queensland, they all have in some sense a unique "market" share with few (or no) competitors, particularly with respect to undergraduate student enrolments, within a certain geographic region (country or state). It is a pretty safe bet that they will be just as viable twenty or thirty years from now. They are not going to be like Kodak.

There are certainly cultural changes, such as the shift from scholarship to money to status.

But, we should not loose sight of the fact that the "core business" and "products" are not changing much. With regard to teaching, I still centre my solid state physics lectures around Ashcroft and Mermin. I may sometimes use powerpoint and get the students to use computer simulations. But what I write on the whiteboard and the struggle for me to explain it and for students to understand it are essentially the same as they were 40 years ago (i.e. before laptops, smart phones, the web, ...) when Ashcroft and Mermin was written.

What about research?

Well good research is just as difficult as it was in pre-web days and before metrics and MBAs. It may be easier to find literature and to communicate with colleagues via email and Skype. But, these are second order effects...

So what are the lessons here?

Foremost, faculty and administrators need to have a long term view.

We should be skeptical about the latest fads and crisis and the focus on investing for the future.

Becoming a good teacher takes many years of practise and experience.

The most significant research requires long term investments in developing and learning new techniques, including many false leads and failures.

Real scholarship takes time.

It is the quality of the faculty, not the administrative policies or the slickness of the marketing, that make a great university.

Attracting, nurturing, and keeping high-quality faculty is a long and slow process that requires stability and long term investments.

What do you think?

How rapidly are things changing?

How much do we need to adapt and change?

No comments:

Post a Comment