Pierre-Gilles de Gennes (1932-2007) was arguably the founder of soft matter as a research field, as recognized by the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1991. After this de Gennes gave many lectures in French high schools, which were then published as a book, Fragile Objects: Soft Matter, Hard Science, and the Thrill of Discovery. Previously, I mentioned the book with regard to whether condensed matter physics is too abstract.

One of many fascinating sections of the book is a chapter entitled, The Imperialism of Mathematics. de Gennes sings the praises of chemistry, and rants about the weaknesses of the French system, laying the blame at the feet of his compatriot Auguste Comte (1798-1857). Comte was one of the first philosophers of modern science and a founder of sociology and of positivism.

Below I reproduce some of the relevant text. When reading it bear in mind that de Gennes was a theoretical physicist and did work that often involved quite abstract mathematics and concepts.

THE "AUGUSTE COMTE" PREJUDICE

I now come to a prejudice typical of French culture, inherited from the positivism of Auguste Comte. This nineteenth-century philosopher achieved some degree of fame by inventing a classification system of the sciences.

At the top of his hierarchy was mathematics; at the bottom was chemistry, which according to him "barely deserved the name of science"; in the middle were astronomy and physics. This classification dismissed out of hand geography and mineralogy, sciences which were declared concrete and descriptive, retaining only those that were theoretical, abstract, and general. The tone was set! It is ironic that this philosophical concept came from an individual who had once written in a letter "The only absolute truth is that everything is relative," and who claimed to be steeped quasi-religiously in factually observable laws, in other words, laws verifiable by experiments.

The "Auguste Comte" prejudice corrupts to this day the teaching of the sciences, the scientific disciplines, and even the scientists themselves. It also contains the seed of contempt for manual labor, which has interfered for years by curbing every attempt at reform to revalue the manual trades and their apprenticeship...

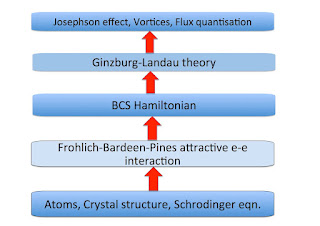

An example comes to mind, of some graduates of the Polytechnic School of Paris attending an advanced program at Orsay to learn solid-state physics. They would often show up convinced that they knew everything on the basis of calculations.

... But the typical Polytechnic graduate I inherited at the time would remain stumped in front of his bare blackboard. One of them finally blurted out (I will never forget his comment): "But, sir, what Hamiltonian should I diagonalize?" He was trying to hang on to theoretical ideas which had no connection whatsoever with this practical problem. This kind of answer explains, in large part, the weakness of French industrial research.

Among all the catastrophes brought about by the positivist prejudice, none is worse than the widespread contempt for chemistry. I have already pointed out the importance of this discipline for our industrial future, the importance of chemists, these marvelously inventive sculptors of molecules, to whom the French teaching establishment does not do nearly enough justice. An undergraduate math major once told me about a teacher who, on opening day, announced: "I personally dislike chemistry, but I have to talk about it. So, I will start by giving you two hours of chemical nomenclature: what the name of an obscure and com- plex molecule is, and the like." At the conclusion of the two hours, the entire class was turned off chemistry for life!

When Lucien Monnerie, the director of studies, and I took over re- sponsibility for courses at the Institute of Physics and Chemistry, we had to wage a determined battle to overcome the antichemistry prejudice. Just before our arrival, the students had organized a strike: they all wanted to become physicists. Slowly, we climbed back up the slope with a series of measures: changing labels, opening up several new channels, turning the entire curriculum upside down, and launching a verbal propaganda campaign. It was rather easy for me to sound persuasive; being a theoretical physicist, nobody could accuse me of protecting my own turf. But it took us 10 years to restore the proper balance.

To anyone who wants to form a more precise idea of chemistry, of the life of a typical chemical engineer, I would advise reading the magnificent collection of essays by Primo Levi, The Periodic Table. They recount real-life stories. They possess an authenticity and a vitality which give a universal impact to the account of an ordinary fact, the description of minute events. It is an excellent antidote to the poison spread by Auguste Comte's classification scheme.