Ben Powell and I have just advertised for a new postdoc position to work with us at the University of Queensland on strongly correlated electron systems.

The full ad is here and people should apply before January 28 through that link.

Friday, December 22, 2017

Monday, December 18, 2017

Are UK universities heading over the cliff?

The Institute of Advanced Study at Durham University has organised a public lecture series, "The Future of the University." The motivation is worthy.

In the face of this rapidly changing landscape, urging instant adaptive response, it is too easy to discount fundamental questions. What is the university now for? What is it, what can it be, what should it be? Are the visions of Humboldt and Newman still valid? If so, how?The poster is a bit bizarre. How should it be interpreted?

Sadly, it is hard for me to even imagine such a public event happening in Australia.

Last week one of the lectures was given by Peter Coveney, a theoretical chemist at University College London, on funding for science. His abstract is a bit of rant with some choice words.

Funding of research in U.K. universities has been changed beyond recognition by the introduction of the so-called "full economic cost model". The net result of this has been the halving of the number of grants funded and the top slicing of up to 50% and beyond of those that are funded straight to the institution, not the grant holder. Overall, there is less research being performed. Is it of higher quality because the overheads are used to provide a first rate environment in which to conduct the research?

We shall trace the pathway of the indirect costs within U.K. universities and look at where these sizeable sums of money have ended up.

The full economic cost model is so attractive to management inside research led U.K. universities that the blueprint is applied willy-nilly to assess the activities of academics, and the value of their research, regardless of where their funding is coming from. We shall illustrate the black hole into which universities have fallen as senior managers seek to exploit these side products of modern scientific research in U.K. Meta activities such as HEFCE's REF consume unconscionable quantities of academics' time, determine university IT and other policies, in the hope of attracting ever more income, but have done little to assist with the prosecution of more and better science. Indeed, it may be argued that they have had the opposite effect.

Innovation, the impact on the economy resulting from U.K. universities' activities, shows few signs of lifting off. We shall explore the reasons for this; they reside in a wilful confusion of universities' roles as public institutions with the overwhelming desire to run them as businesses. Despite the egregious failure of market capitalism in 2008, their management cadres simply cannot stop themselves wanting to ape the private sector.Some of the talk material is in a short article in the Times Higher Education Supplement. The slides for the talk are here. I thank Timothee Joset, who attended the talk, for bringing it to my attention.

Thursday, December 14, 2017

Statistical properties of networks

Today I am giving a cake meeting talk about something a bit different. Over the past year or so I have tried to learn something about "complexity theory", including networks. Here is some of what I have learnt and found interesting. The most useful (i.e. accessible) article I found was a 2008 Physics Today article, The physics of networks by Mark Newman.

The degree of a node, denoted k, is equal to the number of edges connected to that node. A useful quantity to describe real-world networks is the probability distribution P(k); i.e. if you pick a random node it gives the probability that the node has degree k.

Analysis of data from a wide range of networks, from the internet to protein interaction networks, finds that this distribution has a power-law form,

This holds over almost four orders of magnitude.

This is known as a scale-free network, and the exponent is typically between 2 and 3.

This power law is significant for several reasons.

First, it is in contrast to a random network for which P(k) would be a Poisson distribution, which decreases exponentially with large k, with a scale defined by the mean value of k.

Second, if the exponent is less than three, then the variance of k diverges in the limit of an infinite size network, reflecting large fluctuations in the degree.

Third, the "fat tail" means there is a significant probability of "hubs", i.e. nodes that are connected to a large number of other nodes. This reflects the significant spatial heterogeneity of real-world networks. This property has a significant effect on others properties of the network, as I discuss below.

An important outstanding question is do real-world networks self-organise in some sense to lead to the scale-free properties?

A question we do know the answer to is, what happens to the connectivity of the network when some of the nodes are removed?

It depends crucially on the network's degree distribution P(k).

Consider two different node removal strategies.

a. Remove nodes at random.

b. Deliberately target high degree nodes for removal.

It turns out that a random network is equally resilient to both "attacks".

In contrast, a scale-free network is resilient to a. but particularly susceptible to b.

Suppose you want to stop the spread of a disease on a social network. What is the best "vaccination" strategy? For a scale-free network that will be to target the highest degree nodes in the hope of producing "herd immunity".

It's a small world!

This involves the popular notion of "six degrees of separation". If you take two random people on earth then on average one has to just go six steps in "friend of a friend of a friend ..." to connect them. Many find this surprising but, this arises because your social network increases exponentially with the number of steps you take and something like (30)^6 gives the population of the planet.

Newman states that a more surprising result is that people are good at finding the short paths, and Kleinberg showed that the effect only works if the social network has a special form.

How does one identify "communities" in networks?

A quantitative method is discussed in this paper and applied to several social, linguistic, and biological networks.

A topic which is both intellectually fascinating and of great practical significance concerns

This is what epidemiology is all about. However, until recently, almost all mathematical models assumed spatial homogeneity, i.e. that the probability of any individual being infected was equally likely. In reality, it depends on how many other individuals they interact with, i.e. the structure of the social network.

The crucial parameter to understand whether an epidemic will occur turns out to not be the mean degree but the mean squared degree. Newman argues

Epidemic processes in complex networks

Romualdo Pastor-Satorras, Claudio Castellano, Piet Van Mieghem, Alessandro Vespignani

They consider different models for the spread of disease. A key parameter is the infection rate lambda which is the ratio of the transition rates for infection and recovery. This is the SIR [susceptible-infectious-recover] model proposed in 1927 by Kermack and McKendrick [cited almost 5000 times!]. This was one of the first mathematical models for epidemiology.

Behaviour is much richer (and more realistic) if one considers models on a complex network. Then one can observe "phase transitions" and critical behaviour. In the figure below rho is the fraction of infected individuals.

The review is helpful but I would have liked more discussion of real data about practical (e.g. public policy) implications. This field has significant potential because due to internet and mobile phone usage a lot more data is being produced about social networks.

The degree of a node, denoted k, is equal to the number of edges connected to that node. A useful quantity to describe real-world networks is the probability distribution P(k); i.e. if you pick a random node it gives the probability that the node has degree k.

Analysis of data from a wide range of networks, from the internet to protein interaction networks, finds that this distribution has a power-law form,

This holds over almost four orders of magnitude.

This is known as a scale-free network, and the exponent is typically between 2 and 3.

This power law is significant for several reasons.

First, it is in contrast to a random network for which P(k) would be a Poisson distribution, which decreases exponentially with large k, with a scale defined by the mean value of k.

Second, if the exponent is less than three, then the variance of k diverges in the limit of an infinite size network, reflecting large fluctuations in the degree.

Third, the "fat tail" means there is a significant probability of "hubs", i.e. nodes that are connected to a large number of other nodes. This reflects the significant spatial heterogeneity of real-world networks. This property has a significant effect on others properties of the network, as I discuss below.

An important outstanding question is do real-world networks self-organise in some sense to lead to the scale-free properties?

A question we do know the answer to is, what happens to the connectivity of the network when some of the nodes are removed?

It depends crucially on the network's degree distribution P(k).

Consider two different node removal strategies.

a. Remove nodes at random.

b. Deliberately target high degree nodes for removal.

It turns out that a random network is equally resilient to both "attacks".

In contrast, a scale-free network is resilient to a. but particularly susceptible to b.

Suppose you want to stop the spread of a disease on a social network. What is the best "vaccination" strategy? For a scale-free network that will be to target the highest degree nodes in the hope of producing "herd immunity".

It's a small world!

This involves the popular notion of "six degrees of separation". If you take two random people on earth then on average one has to just go six steps in "friend of a friend of a friend ..." to connect them. Many find this surprising but, this arises because your social network increases exponentially with the number of steps you take and something like (30)^6 gives the population of the planet.

Newman states that a more surprising result is that people are good at finding the short paths, and Kleinberg showed that the effect only works if the social network has a special form.

How does one identify "communities" in networks?

A quantitative method is discussed in this paper and applied to several social, linguistic, and biological networks.

A topic which is both intellectually fascinating and of great practical significance concerns

This is what epidemiology is all about. However, until recently, almost all mathematical models assumed spatial homogeneity, i.e. that the probability of any individual being infected was equally likely. In reality, it depends on how many other individuals they interact with, i.e. the structure of the social network.

The crucial parameter to understand whether an epidemic will occur turns out to not be the mean degree but the mean squared degree. Newman argues

Consider a hub in a social network: a person having, say, a hundred contacts. If that person gets sick with a certain disease, then he has a hundred times as many opportunities to pass the disease on to others as a person with only one contact. However, the person with a hundred contacts is also more likely to get sick in the first place because he has a hundred people to catch the disease from. Thus such a person is both a hundred times more likely to get the disease and a hundred times more likely to pass it on, and hence 10 000 times more effective at spreading the disease than is the person with only one contact.I found the following Rev. Mod. Phys. from 2015 helpful.

Epidemic processes in complex networks

Romualdo Pastor-Satorras, Claudio Castellano, Piet Van Mieghem, Alessandro Vespignani

They consider different models for the spread of disease. A key parameter is the infection rate lambda which is the ratio of the transition rates for infection and recovery. This is the SIR [susceptible-infectious-recover] model proposed in 1927 by Kermack and McKendrick [cited almost 5000 times!]. This was one of the first mathematical models for epidemiology.

Behaviour is much richer (and more realistic) if one considers models on a complex network. Then one can observe "phase transitions" and critical behaviour. In the figure below rho is the fraction of infected individuals.

In a 2001 PRL [cited more than 4000 times!] it was shown using a "degree-based mean-field theory" that the critical value for lambda is given by

In a scale-free network the second moment diverges and so there is no epidemic threshold, i.e. for an infinitely small infection rate and epidemic can occur.The review is helpful but I would have liked more discussion of real data about practical (e.g. public policy) implications. This field has significant potential because due to internet and mobile phone usage a lot more data is being produced about social networks.

Friday, December 8, 2017

Four distinct responses to the cosmological constant problem

One of the biggest problems in theoretical physics is to explain why the cosmological constant has the value that it does.

There are two aspects to the problem.

The first problem is that the value is so small, 120 orders of magnitude smaller than what one estimates based on the quantum vacuum energy!

The second problem is that the value seems to be finely tuned (to 120 significant figures!) to the value of the mass energy.

The problems and proposed (unsuccessful) solutions are nicely reviewed in an article written in 2000 by Steven Weinberg.

There seem to be four distinct responses to this problem.

1. Traditional scientific optimism.

A yet to be discovered theory will explain all this.

2. Fatalism.

That is just the way things are. We will never understand it.

3. Teleology and Design.

God made it this way.

4. The Multiverse.

This finely tuned value is just an accident. Our universe is one of zillions possible. Each has different fundamental constants.

It is is amazing how radical 2, 3, and 4, are.

I have benefited from some helpful discussions about this with Robert Mann. There is a Youtube video where we discuss the multiverse. Some people love the video. Others think it incredibly boring. I think we are both too soft on the multiverse.

There are two aspects to the problem.

The first problem is that the value is so small, 120 orders of magnitude smaller than what one estimates based on the quantum vacuum energy!

The second problem is that the value seems to be finely tuned (to 120 significant figures!) to the value of the mass energy.

The problems and proposed (unsuccessful) solutions are nicely reviewed in an article written in 2000 by Steven Weinberg.

There seem to be four distinct responses to this problem.

1. Traditional scientific optimism.

A yet to be discovered theory will explain all this.

2. Fatalism.

That is just the way things are. We will never understand it.

3. Teleology and Design.

God made it this way.

4. The Multiverse.

This finely tuned value is just an accident. Our universe is one of zillions possible. Each has different fundamental constants.

It is is amazing how radical 2, 3, and 4, are.

I have benefited from some helpful discussions about this with Robert Mann. There is a Youtube video where we discuss the multiverse. Some people love the video. Others think it incredibly boring. I think we are both too soft on the multiverse.

Thursday, December 7, 2017

Superconductivity is emergent. So what?

Superconductivity is arguably the most intriguing example of emergent phenomena in condensed matter physics. The introduction to an endless stream of papers and grant applications mention this. But, so what? Why does this matter? Are we just invoking a "buzzword" or does looking at superconductivity in this way actually help our understanding?

When we talk about emergence I think there are three intertwined aspects to consider: phenomena, concepts, and effective Hamiltonians.

For example, for a superconductor, the emergent phenomena include zero electrical resistance, the Meissner effect, and the Josephson effect.

In a type-II superconductor in an external magnetic field, there are also vortices and quantisation of the magnetic flux through each vortex.

The main concept associated with the superconductivity is the spontaneously broken symmetry.

This is described by an order parameter.

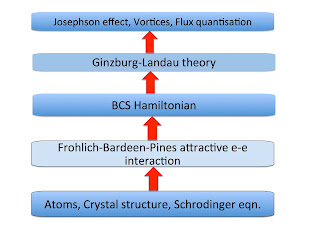

The figure below shows the different hierarchies of scale associated with superconductivity in elemental metals. The bottom four describe effective Hamiltonians.

The hierarchy above was very helpful (even if not explicitly stated) in the development of the theory of superconductivity. The validity of the BCS Hamiltonian was supported by the fact that it could produce the Ginzburg-Landau theory (as shown by Gorkov) and that the attractive interaction in the BCS Hamiltonian (needed to produce Cooper pairing) could be produced from screening of the electron-phonon interaction by the electron-electron interaction, as shown by Frohlich and Bardeen and Pines.Have I missed something?

Tuesday, November 21, 2017

How do you run a meaningful and effective consultation?

It is now quite common for university management and funding agencies to run "consultations" where they interact with members of the "community" and "stakeholders". An example, I recently attended at my university was one concerning the university developing a "Mental Health Strategy".

Some departments run "retreats" for staff members with similar aims.

For reasons I describe below, I think such events vary greatly in their value and effectiveness.

I write this because I would like to hear from readers what they think are important ingredients for an effective and meaningful consultation.

My interest is partly because my wife and I were asked by a NGO and a philanthropic organisation to facilitate several consultations with a view to future grant-making initiatives.

My literature search for "best practises" did not yield much.

But here are two resources we did find helpful.

How Employees Shaped Strategy at the New York Public Library

[Published in the Harvard Business Review]

Appreciative Inquiry

Both of these focus on finding a balance between "bottom-up" rather than a "top-down" approach.

They focus on positive things that may be already happening and building on them rather than focussing on problems.

A while ago I heard a talk by a faculty member who previously was Chief of Staff for a state Governor. He mentioned that one of worst things he had to do in that role was to run community "consultations" about "proposed" new government initiatives and policies. Unfortunately, the government had already made a decision but was merely conducting these events to give the appearance of consulting people who would be affected. A sad thing is that some would consider that Governor was one of the best that the state has had.

In a blog post, Best practice of top academic departments, Rohan Pitchford from the ANU School of Economics laments that in Australian universities

Here are a few things I have observed.

First, rearrange the furniture. This says a lot about the power and communication dynamics in the room. A traditional lecture theatre means people can't see each other and that everyone is looking at the "presenter" who has the power and presents pre-packaged solutions. In contrast, a flat floor with groups of people around circular tables which are used for break out discussion groups, suggests something quite different. My wife taught me this. I also heard from Jenny Charteris (who does this for a living) that this is the first lesson of Facilitation 101.

It was interesting that the UQ Mental Health consultation was done in a good room like I describe above and I think this did facilitate more discussion, including after the meeting. I don't know if this was by intent or whether it was just the room that was available.

Second, it is important that people are heard and feel heard.

In many Australian universities, staff surveys have shown that the vast majority of staff say that "senior management does not listen to other staff". I have also seen instances where someone up the front exhibited what seemed "fake empathy". "I hear you, but ...." and later implemented policies that were contrary to what happened at the meeting.

Third, allow plenty of time for discussion, both in small and large groups. It is also to break up the small groups along different demographic lines.

Fourth, interaction both before and after any meeting is valuable. This also means providing different forums and means of communication, from anonymous comments on a website to public discussions with large groups. I thought it was good that for the UQ Mental Health consultation they said they had already run some small focus groups to get ideas.

What do you think are important ingredients for a meaningful and effective consultation?

Some departments run "retreats" for staff members with similar aims.

For reasons I describe below, I think such events vary greatly in their value and effectiveness.

I write this because I would like to hear from readers what they think are important ingredients for an effective and meaningful consultation.

My interest is partly because my wife and I were asked by a NGO and a philanthropic organisation to facilitate several consultations with a view to future grant-making initiatives.

My literature search for "best practises" did not yield much.

But here are two resources we did find helpful.

How Employees Shaped Strategy at the New York Public Library

[Published in the Harvard Business Review]

Appreciative Inquiry

Both of these focus on finding a balance between "bottom-up" rather than a "top-down" approach.

They focus on positive things that may be already happening and building on them rather than focussing on problems.

A while ago I heard a talk by a faculty member who previously was Chief of Staff for a state Governor. He mentioned that one of worst things he had to do in that role was to run community "consultations" about "proposed" new government initiatives and policies. Unfortunately, the government had already made a decision but was merely conducting these events to give the appearance of consulting people who would be affected. A sad thing is that some would consider that Governor was one of the best that the state has had.

In a blog post, Best practice of top academic departments, Rohan Pitchford from the ANU School of Economics laments that in Australian universities

Over the last 15-20 years academic school meetings have gone from rambling and unstructured brawls to dull “executive infomercials”. The former led to marathon meetings. The current model has led to a middle-management culture that often does not take advantage of the very valuable specialists skills of talented, highly trained (and experienced) scholars in the department. Nor does it allow for reasonable checks and balances on the powers of the executive–something that is vital for the management of any group of academics.Australian indigenous communities face many challenges. I recently heard one of their leaders say they were so sick of "white fellas" coming and running "consultations" aimed at finding "solutions" to their problems. He said the negative focus was actually dis-empowering the community, sucking away the energy and confidence to address their problems. They needed a more positive approach that focussed on some of the good things that they were doing and how they could build on those.

Here are a few things I have observed.

First, rearrange the furniture. This says a lot about the power and communication dynamics in the room. A traditional lecture theatre means people can't see each other and that everyone is looking at the "presenter" who has the power and presents pre-packaged solutions. In contrast, a flat floor with groups of people around circular tables which are used for break out discussion groups, suggests something quite different. My wife taught me this. I also heard from Jenny Charteris (who does this for a living) that this is the first lesson of Facilitation 101.

It was interesting that the UQ Mental Health consultation was done in a good room like I describe above and I think this did facilitate more discussion, including after the meeting. I don't know if this was by intent or whether it was just the room that was available.

Second, it is important that people are heard and feel heard.

In many Australian universities, staff surveys have shown that the vast majority of staff say that "senior management does not listen to other staff". I have also seen instances where someone up the front exhibited what seemed "fake empathy". "I hear you, but ...." and later implemented policies that were contrary to what happened at the meeting.

Third, allow plenty of time for discussion, both in small and large groups. It is also to break up the small groups along different demographic lines.

Fourth, interaction both before and after any meeting is valuable. This also means providing different forums and means of communication, from anonymous comments on a website to public discussions with large groups. I thought it was good that for the UQ Mental Health consultation they said they had already run some small focus groups to get ideas.

What do you think are important ingredients for a meaningful and effective consultation?

Monday, November 20, 2017

I am not that Ross MacKenzie

Today the Australian Medical Journal published an article

Legal does not mean unaccountable: suing tobacco companies to recover health care costs

Ross MacKenzie, Eric LeGresley and Mike Daube

This is getting some press and community attention.

For the public record, I am not one of the authors. I am Ross McKenzie.

Yesterday, I got an invitation to do an interview with a radio station in New Zealand!

Now, I just received the following hate mail.

Legal does not mean unaccountable: suing tobacco companies to recover health care costs

Ross MacKenzie, Eric LeGresley and Mike Daube

This is getting some press and community attention.

For the public record, I am not one of the authors. I am Ross McKenzie.

Yesterday, I got an invitation to do an interview with a radio station in New Zealand!

Now, I just received the following hate mail.

Pity that you don't advocate for the government to recoup alcohol costs from companies, who have caused much more damage to drunks and others, you intellectual pigmy

Monday, November 13, 2017

Two important principles of time management

1. Delegate

2. It can wait.

These are also conducive to good mental health.

The second is not a mandate for procrastination.

Rather it is a mandate to be pro-active rather than reactive, to set and stick to priorities, to not let the squeaky wheel get the most oil, to let people solve their own problems, ....

I often feel pressure to get a long list of things done as soon as possible. This is not good for my stress level and mental health. However, if I can calm down and let things go, and come back to them later, I will have a better sense of perspective.

I don't claim to have the best time management. Some earlier thoughts are here.

2. It can wait.

These are also conducive to good mental health.

The second is not a mandate for procrastination.

Rather it is a mandate to be pro-active rather than reactive, to set and stick to priorities, to not let the squeaky wheel get the most oil, to let people solve their own problems, ....

I often feel pressure to get a long list of things done as soon as possible. This is not good for my stress level and mental health. However, if I can calm down and let things go, and come back to them later, I will have a better sense of perspective.

I don't claim to have the best time management. Some earlier thoughts are here.

Tuesday, November 7, 2017

Social qualities emerge from multiple interactions at multiple scales

Different qualities are used to describe and characterise societies: civil, fair, intolerant, racist, corrupt, free, ….

Two big questions are:

How does a society make a transition between from a bad quality and a good quality?

What kind of initiatives can induce changes?

Initiatives can be individual or collective, political or economic, local or national, ...

For example, how does reduce corruption, which is endemic in many Majority world countries?

Or in the USA, why is public debate losing civility?

I think it is helpful to acknowledge the complexity of these issues. They have some similarity to wicked problems. They are problems that involve multiple interactions at multiple scales. Some of these interactions are competing and frustrated (in the spin glass sense!) and initiatives can lead to unintended consequences.

Whether you look at societies from a sociological, cultural, geographical, political, or economic perspective they involve multiple scales. For example, at the political level, one goes from local to city to state to national governments to the United Nations. In some countries corruption (bribes, extortion, nepotism, tax evasion,…) occurs at all levels. A policeman demands a bribe for a traffic violation. A university administrator changes records so his nephew, a mediocre student, can be admitted to medical school. The president of the country moves millions of dollars in foreign aid money into an off-shore bank account….

These phenonmena occur at multiple scales and involve multiple interactions. For example, an individual citizen will interact with many levels of government, and government agencies, and with each may be involved or impacted by a corrupt interaction.

Civility (respect, graciousness, politeness, listening) or uncivility (disrespect, rudeness, contempt, shouting) also occurs at many levels. These range from everyday conversations, comments on Facebook, to debate in parliament, to the Twitter feed of the President of the USA.

Michel Foucault, is one of the most influential (for better or worse) scholars in the humanities from the 20th century. He is particularly well known for his arguments that power operates at many levels and in many different ways in societies.

I find a multi-scale perspective helpful because it undercuts two extreme but common views concerning how we address significant social problems.

One view is the “top-down” perspective that if we just have the right national leader and the right laws a problem will be solved. This is argued for a whole range of issues ranging from corruption to sexual harassment, to “hate speech”.

The other extreme is the “bottom-up” view that the problem can be solved by individuals just making the right choices. Each individual should be polite to others and not give or take bribes. We need both approaches.

Moreover, I believe we need initiatives at all levels and interactions.

The importance of the absence of the intermediate scales (and the associated concept of social capital) was highlighted in Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, by the Harvard political scientist Robert D. Putnam.

An example of a multi-scale perspective is in the Oxfam book, From Poverty to Power: How active citizens and effective states can change the world.

A question that is both practically important and intellectually fascinating is:

What are the critical parameters and their values at which a society undergoes a “phase transition”?

Such a question is addressed in

The Epidemics of Corruption

Ph. Blanchard, A. Krueger, T. Krueger, P. Martin

The figure is from a paper, Small-World Networks of Corruption.

Two big questions are:

How does a society make a transition between from a bad quality and a good quality?

What kind of initiatives can induce changes?

Initiatives can be individual or collective, political or economic, local or national, ...

For example, how does reduce corruption, which is endemic in many Majority world countries?

Or in the USA, why is public debate losing civility?

I think it is helpful to acknowledge the complexity of these issues. They have some similarity to wicked problems. They are problems that involve multiple interactions at multiple scales. Some of these interactions are competing and frustrated (in the spin glass sense!) and initiatives can lead to unintended consequences.

Whether you look at societies from a sociological, cultural, geographical, political, or economic perspective they involve multiple scales. For example, at the political level, one goes from local to city to state to national governments to the United Nations. In some countries corruption (bribes, extortion, nepotism, tax evasion,…) occurs at all levels. A policeman demands a bribe for a traffic violation. A university administrator changes records so his nephew, a mediocre student, can be admitted to medical school. The president of the country moves millions of dollars in foreign aid money into an off-shore bank account….

These phenonmena occur at multiple scales and involve multiple interactions. For example, an individual citizen will interact with many levels of government, and government agencies, and with each may be involved or impacted by a corrupt interaction.

Civility (respect, graciousness, politeness, listening) or uncivility (disrespect, rudeness, contempt, shouting) also occurs at many levels. These range from everyday conversations, comments on Facebook, to debate in parliament, to the Twitter feed of the President of the USA.

Michel Foucault, is one of the most influential (for better or worse) scholars in the humanities from the 20th century. He is particularly well known for his arguments that power operates at many levels and in many different ways in societies.

I find a multi-scale perspective helpful because it undercuts two extreme but common views concerning how we address significant social problems.

One view is the “top-down” perspective that if we just have the right national leader and the right laws a problem will be solved. This is argued for a whole range of issues ranging from corruption to sexual harassment, to “hate speech”.

The other extreme is the “bottom-up” view that the problem can be solved by individuals just making the right choices. Each individual should be polite to others and not give or take bribes. We need both approaches.

Moreover, I believe we need initiatives at all levels and interactions.

The importance of the absence of the intermediate scales (and the associated concept of social capital) was highlighted in Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, by the Harvard political scientist Robert D. Putnam.

An example of a multi-scale perspective is in the Oxfam book, From Poverty to Power: How active citizens and effective states can change the world.

A question that is both practically important and intellectually fascinating is:

What are the critical parameters and their values at which a society undergoes a “phase transition”?

Such a question is addressed in

The Epidemics of Corruption

Ph. Blanchard, A. Krueger, T. Krueger, P. Martin

The figure is from a paper, Small-World Networks of Corruption.

Tuesday, October 24, 2017

My recent mental health reading

Mental issues have been on my radar for the past few months, mainly for three reasons. First, I am coming back (very positively) from a low over the past year. Second, I continue to have many conversations with people who have struggled with the issue. Third, University of Queensland has decided to develop a "Mental Health Strategy" for students and staff.

Last week I went to a public consultation about a draft document for UQ. (I was on leave from work, but thought it so important I went on campus). I read the document carefully, spoke out at the meeting, and also sent some email feedback.

More on that later, maybe...

Australian universities seem to have discovered the issue following the publication of a report, concerning student mental health. The "strategy" for ANU is here.

Here are a few valuable pieces that have "come across my desk" in the last few months.

Santa Ono, President of the University of British Columbia, and a distinguished medical researcher is a passionate advocate and speaks publically, about his own struggles, including several suicide attempts.

On PBS Wellread [recommended by my mother-in-law], I watched a fascinating interview with Tracy Kidder, a Pulitzer Prize winner, whose latest book is a profile of Paul English, a wealthy software entrepreneur who suffers from bipolar disorder. A Truck Full Of Money.

The ‘Madman’ Is Back in the Building is a moving Opinion piece about the personal experience of a lawyer who had a psychotic breakdown at work and then struggled as he went back to work after 90 days leave.

There is a BBC article about a recent UK study commissioned by the Prime Minister

'Depression lost me my job': How mental health costs up to 300,000 jobs a year

Mental health also features in a Nature editorial

Many junior scientists need to take a hard look at their job prospects. Permanent jobs in academia are scarce, and someone needs to let PhD students know.

Last week I went to a public consultation about a draft document for UQ. (I was on leave from work, but thought it so important I went on campus). I read the document carefully, spoke out at the meeting, and also sent some email feedback.

More on that later, maybe...

Australian universities seem to have discovered the issue following the publication of a report, concerning student mental health. The "strategy" for ANU is here.

Here are a few valuable pieces that have "come across my desk" in the last few months.

Santa Ono, President of the University of British Columbia, and a distinguished medical researcher is a passionate advocate and speaks publically, about his own struggles, including several suicide attempts.

On PBS Wellread [recommended by my mother-in-law], I watched a fascinating interview with Tracy Kidder, a Pulitzer Prize winner, whose latest book is a profile of Paul English, a wealthy software entrepreneur who suffers from bipolar disorder. A Truck Full Of Money.

The ‘Madman’ Is Back in the Building is a moving Opinion piece about the personal experience of a lawyer who had a psychotic breakdown at work and then struggled as he went back to work after 90 days leave.

There is a BBC article about a recent UK study commissioned by the Prime Minister

'Depression lost me my job': How mental health costs up to 300,000 jobs a year

Mental health also features in a Nature editorial

Many junior scientists need to take a hard look at their job prospects. Permanent jobs in academia are scarce, and someone needs to let PhD students know.

More than one-quarter of the Ph.D students who responded listed mental health as an area of concern, and 45% of those said they had sought help for anxiety or depression caused by their PhD. One-third of those got useful help from their institution (which of course means that two-thirds did not).

Thursday, October 5, 2017

Which single verb describes the mission of universities?

Think!

Research is all about thinking about the world we live in; whether it is genetics, cosmology, literature, engineering, or economics, ...

Reality is stratified and one observes different phenomena in different systems. As a result, one needs to think in distinct ways in order to develop concepts, laws, and methodologies for each stratum.

Note that thinking is central to experiments: thinking how to design the experiment and apparatus, and how to analyse the data produced and relate it to theory.

This is why we have disciplines. Each discipline involves a disciplined way of thinking.

Teaching is all about helping students learn how to think.

For specific disciplines, it involves learning how to think in a particular way.

Thinking like a condensed matter physicist is an art to learn.

Similarly, thinking like an economist is a unique way of thinking.

If this is the mission of modern universities are they successful?

On one level they have been incredibly successful.

Almost all the disciplines and knowledge we have were created in universities.

These ways of thinking have been incredibly productive and revealed things we might never have anticipated or dreamed of. Whether it is the genetic code, quantum field theory, game theory, or studies of ancient histories and cultures, ....

Furthermore, universities have really taught many students to think critically and creatively, not just about academic matters. University graduates have used their thinking skills in constructive ways, whether in inventions, starting companies, journalism, politics, philanthropy, ...

It should be acknowledged that this education does not just occur in the classroom but in informal contexts and involvement in student clubs and societies.

However, when you consider the resources that have been expended globally, both in teaching and research, you have to wonder whether universities are now failing at their mission.

This is reflected in a sparsity of critical thinking on many levels and in many contexts.

In the Majority World, universities try to mimic Western ones, at the superficial level of structures and curriculum. However, largely they focus on rote learning and not questioning teachers. This tragedy is captured with humour in my favourite Bollywood movie scene. Not only are students not taught how to think, they are actually taught not to think at all!

Yet, Elite universities now have a lot to answer for. The administration has become decoupled from the faculty and so we have metric madness and mindless marketing. Many of the statements or decision making processes (e.g. ignoring uncertainties, listing journal impact factors to 4 significant figures or cherry picking data to enhance the "ranking" of an institution) would be not be allowed in a freshman tutorial or lab.

Yet faculty are not without fault. Critical analysis will be avoided if publishing in a luxury journal is on the horizon. Then there is the hype of faculty about their latest research, whether in grant applications or public relations.

There are countless other ideas about what the mission of the university should be: training graduates for high paying jobs, wealth creation, enhancing national security, elite sports, industrial research, creating good citizens, ...

Many of these alternative missions are debatable, but regardless, they should be subordinate to the thinking mission.

Key to the thinking mission is academic freedom. Faculty and students need to be free to think what they want about what they want (within certain civil and resource constraints). Political interference and commercial interests inhibit such thinking.

It is interesting that Terry Eagleton, considers that the primary mission of universities is to critique society.

I thank Vinoth Ramachandra for teaching me this basic but crucial idea.

Research is all about thinking about the world we live in; whether it is genetics, cosmology, literature, engineering, or economics, ...

Reality is stratified and one observes different phenomena in different systems. As a result, one needs to think in distinct ways in order to develop concepts, laws, and methodologies for each stratum.

Note that thinking is central to experiments: thinking how to design the experiment and apparatus, and how to analyse the data produced and relate it to theory.

This is why we have disciplines. Each discipline involves a disciplined way of thinking.

Teaching is all about helping students learn how to think.

For specific disciplines, it involves learning how to think in a particular way.

Thinking like a condensed matter physicist is an art to learn.

Similarly, thinking like an economist is a unique way of thinking.

If this is the mission of modern universities are they successful?

On one level they have been incredibly successful.

Almost all the disciplines and knowledge we have were created in universities.

These ways of thinking have been incredibly productive and revealed things we might never have anticipated or dreamed of. Whether it is the genetic code, quantum field theory, game theory, or studies of ancient histories and cultures, ....

Furthermore, universities have really taught many students to think critically and creatively, not just about academic matters. University graduates have used their thinking skills in constructive ways, whether in inventions, starting companies, journalism, politics, philanthropy, ...

It should be acknowledged that this education does not just occur in the classroom but in informal contexts and involvement in student clubs and societies.

However, when you consider the resources that have been expended globally, both in teaching and research, you have to wonder whether universities are now failing at their mission.

This is reflected in a sparsity of critical thinking on many levels and in many contexts.

In the Majority World, universities try to mimic Western ones, at the superficial level of structures and curriculum. However, largely they focus on rote learning and not questioning teachers. This tragedy is captured with humour in my favourite Bollywood movie scene. Not only are students not taught how to think, they are actually taught not to think at all!

Yet, Elite universities now have a lot to answer for. The administration has become decoupled from the faculty and so we have metric madness and mindless marketing. Many of the statements or decision making processes (e.g. ignoring uncertainties, listing journal impact factors to 4 significant figures or cherry picking data to enhance the "ranking" of an institution) would be not be allowed in a freshman tutorial or lab.

Yet faculty are not without fault. Critical analysis will be avoided if publishing in a luxury journal is on the horizon. Then there is the hype of faculty about their latest research, whether in grant applications or public relations.

There are countless other ideas about what the mission of the university should be: training graduates for high paying jobs, wealth creation, enhancing national security, elite sports, industrial research, creating good citizens, ...

Many of these alternative missions are debatable, but regardless, they should be subordinate to the thinking mission.

Key to the thinking mission is academic freedom. Faculty and students need to be free to think what they want about what they want (within certain civil and resource constraints). Political interference and commercial interests inhibit such thinking.

It is interesting that Terry Eagleton, considers that the primary mission of universities is to critique society.

I thank Vinoth Ramachandra for teaching me this basic but crucial idea.

Thursday, September 28, 2017

Emergence in the Game of Life

How do complex structures emerge from simple systems?

How do you define emergence?

Conway's Game of life is a popular and widely studied version of cellular automata. It is based on four simple rules for the evolution of a two-dimensional grid of squares that can either be dead or alive. What is amazing is that distinct patterns: still lifes, oscillators, and spaceships can emerge.

Gosper's glider gun is shown below.

What does this have to do with strongly correlated electron systems?

The similarity is that one starts with extremely simple "rules": a crystal structure plus Coloumb's law and the Schrodinger equation (Laughlin and Pines' Theory of Everything) and complex structures emerge: quasi-particles, broken symmetry states, topological order, non-Fermi liquids, ...

Recently, Sophia Kivelson and Steven Kivelson [daughter and father] proposed the following definition:

The definition also disagrees with Michael Polanyi, who argued that language and grammar are emergent.

How do you define emergence?

Conway's Game of life is a popular and widely studied version of cellular automata. It is based on four simple rules for the evolution of a two-dimensional grid of squares that can either be dead or alive. What is amazing is that distinct patterns: still lifes, oscillators, and spaceships can emerge.

Gosper's glider gun is shown below.

What does this have to do with strongly correlated electron systems?

The similarity is that one starts with extremely simple "rules": a crystal structure plus Coloumb's law and the Schrodinger equation (Laughlin and Pines' Theory of Everything) and complex structures emerge: quasi-particles, broken symmetry states, topological order, non-Fermi liquids, ...

Recently, Sophia Kivelson and Steven Kivelson [daughter and father] proposed the following definition:

An emergent behavior of a physical system is a qualitative property that can only occur in the limit that the number of microscopic constituents tends to infinity.I think this would mean the properties above would not be classified as emergent. I am not sure I agree. I think I still prefer older broader definitions such as that of Michael Berry in terms of singular expansions or that of P. Luisi.

The definition also disagrees with Michael Polanyi, who argued that language and grammar are emergent.

Saturday, September 23, 2017

My ambivalence to anonymous blog comments

Although this blog has a wide readership one thing it struggles with is to attract many comments, and particularly much back and forth discussion. Sometimes people tell me that this is just because it is not provocative or controversial enough.

A while ago I changed the settings to allow anonymous comments and this has led to an increase in comments which is encouraging. However, I do have some ambivalence about this.

Ideally, any comment and opinion should be judged on the merits of its content not based on who is giving it. We should beware of arguments from authority. On the other hand, that is not the way most of us think and act. We do give some weight to the author. For example, an anonymous commenter says "I am a physicist and I am a climate change skeptic" it does not have the same weight as the opinion of a respected physicist who has relevant expertise.

I am also concerned that people are not willing to take the risk of being publically identified with their views. This does not just reflect on the commenter but also reflects poorly on the scientific and academic community. Why are people so hesitant? Is the community so intolerant of controversial views?

Here I should say I am very sympathetic to some peoples nervousness. At least twice, I suggested to younger colleagues who did not have permanent jobs that they delete specific comments they made on the blog that were critical of the "establishment".

I welcome discussion.

Nevertheless, please don't let my ambivalence stop you making comments.

Wednesday, September 20, 2017

An ode to long service leave

Australia has many unique things besides kangaroos and koalas. Long service leave (LSL) is a generous and egalitarian feature of the "welfare" state. After ten years working for the same employer [or the same sector such as government universities] an employee is granted three months fully paid vacation. (The exact terms and conditions vary slightly between states and employers). LSL is available to all full-time employees, regardless of whether they are janitor or CEO. This is in addition to four (plus) weeks of annual leave and for faculty in addition to "sabbaticals" [called Special Studies Program in my university]. If an employee resigns any unused balance is "cashed out".

University faculty work hard and some are workaholics. Many don't even take their allotted annual vacation, let alone LSL. Balances carry over each year and so some faculty have large balances. The "accountants" (who basically run the university) don't like this because LSL is a "liability" on their spreadsheets. If all of the faculty with large balances resigned at the same time the university would have to "cash" them out and there would be no money available to hire replacements for several months. Who would do the teaching, research, and admin? The university would grind to a halt....

However, this is pretty silly because the likelihood of massive simultaneous resignations of this particular group is extremely unlikely. When an individual does resign one can always wait a while to rehire and others absorb their "workload". Furthermore, this is likely to happen anyway, because replacing people, particularly senior ones, takes a while anyway.

Nevertheless, because the accountants rule, faculty are put under pressure to take LSL and recreation leave (vacation) if they have large balances. Specifically at UQ, when a staff member has a balance of more than 15 weeks of LSL they can be "directed" to take leave to reduce their balance. In fact, we now receive emails from the Executive Dean telling us that in our annual appraisal (performance review) we have to discuss the issue and come up with a written plan of how we will reduce our leave balance. On one level this is fine. However, on another level, this just reflects skewed priorities. We do not get explicit instructions and reminders (and threats) to discuss and plan how to engage better with students, set more challenging assessment, focus on research quality rather than quantity, be critical about metrics, ...

So what do people do with their LSL?

Is it actually in the best interests of the university for people to take it?

Here are some specific examples I am aware of.

1. Keep going to your office and doing research but no teaching or admin. The problem is that legally the university does not want this as they don't have liability insurance for you while on campus.

2. Treat it as a sabbatical and visit another institution. The problem is that you are on vacation as far as the university is concerned and so cannot use grant money for travel.

3. Have a long vacation and come back refreshed and motivated.

4. Have a great vacation and decide to retire early.

5. Spend the time looking for a new job. During this time many things and important decisions are left in limbo, before the employee eventually leaves.

Although most of these options may be good for the employee, they may not be the best thing for the employer. Thus, in the bigger scheme of things, forcing people to take LSL is debatable.

There is more to an institution than spreadsheets....

Having said all this I should say that I am really enjoying my LSL. The picture below is from a kayak trip in the San Juan Islands, near my mother-in-law's house, which also features sunsets such as above.

Wednesday, September 13, 2017

The rise of BS in science and academia

I never thought I would write a blog post with such a word in it.

In today’s Seattle Times there is an editorial about fake news and an opinion piece, How to fine-tune your BS meter, by Jevin West.

At the University of Washington, West and Carl Bergstrom, have started a course entitled, Calling BS: Data reasoning for the digital age.

West states:

particularly that appear in luxury journals, as “just BS”.

A good question is what criteria should we use to distinguish between uncritical enthusiasm, marketing, hype, and BS?

I first thought of writing a post on this subject when I encountered this video clip from CNN.

I thought, “Wow! Who is this commentator?” Maybe I should have known, but I learned that Fareek Zakaria has quite a following, a Ph.D. in Political Science from Harvard, and is rightly viewed as a serious commentator, regardless of whether you agree with his political leanings.

The commentary is based on a number one New York Times bestseller, On BS by Harry Frankfurt, a distinguished Princeton philosopher.

In today’s Seattle Times there is an editorial about fake news and an opinion piece, How to fine-tune your BS meter, by Jevin West.

At the University of Washington, West and Carl Bergstrom, have started a course entitled, Calling BS: Data reasoning for the digital age.

West states:

Our philosophy is that you don’t need a Ph.D. in statistics or computer science to call BS on the vast majority of data bullshit. If you think clearly about what might be wrong with the data someone is using and what might be wrong about the interpretation of their results, you’ll catch a huge fraction of the bullshit without ever going into the mathematical details.

Unfortunately, this applies to science as much as to Fake News. On his blog, Peter Woit discusses the rise of Fake Physics.Science is in trouble when the word I most often hear associated with the name of a particular Ivy League science Professor is BS. Furthermore, in many contexts, I hear people dismiss specific papers,

particularly that appear in luxury journals, as “just BS”.

A good question is what criteria should we use to distinguish between uncritical enthusiasm, marketing, hype, and BS?

I first thought of writing a post on this subject when I encountered this video clip from CNN.

I thought, “Wow! Who is this commentator?” Maybe I should have known, but I learned that Fareek Zakaria has quite a following, a Ph.D. in Political Science from Harvard, and is rightly viewed as a serious commentator, regardless of whether you agree with his political leanings.

The commentary is based on a number one New York Times bestseller, On BS by Harry Frankfurt, a distinguished Princeton philosopher.

Saturday, September 2, 2017

Debating emergence and reductionism

As part of a TV documentary, Why are we here? produced by Ard Louis and David Malone there is a nice series of interviews where emergence is discussed by George Ellis, Peter Atkins, and Denis Noble.

I can't seem to embed the interviews here and so have put in links to short clips.

George Ellis discusses the difference between weak and strong emergence and his attitude to each.

In separate clips, Denis Noble discusses emergence and reductionism in biology.

Peter Atkins, a hardcore reductionist, IMHO does not seem to seriously engage with the issue.

I can't seem to embed the interviews here and so have put in links to short clips.

George Ellis discusses the difference between weak and strong emergence and his attitude to each.

In separate clips, Denis Noble discusses emergence and reductionism in biology.

Peter Atkins, a hardcore reductionist, IMHO does not seem to seriously engage with the issue.

Thursday, August 31, 2017

Did Schrodinger's cat explore Tolkien's garden?

In 1935 Schrodinger wrote his famous paper (with the cat) introducing the term entanglement, in response to the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paper published earlier that year.

When Schrodinger wrote the paper he was living in a house on Northmoor Road, Oxford. This was the same house where Schrodinger learned he had been awarded the Nobel Prize.

I recently learned some fascinating historical trivia.

Schrodinger was a neighbour of J.R.R. Tolkien, who during that time was finishing up work on The Hobbit.

It would be nice to see this landmark honoured, such as the one on Tolkien's house. However, it seems Schrodinger's house does not meet the criteria of Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Board, because he lived there for three years, less than the required minimum of five years.

Another option would be a plaque of the Institute of Physics, such as this one.

When Schrodinger wrote the paper he was living in a house on Northmoor Road, Oxford. This was the same house where Schrodinger learned he had been awarded the Nobel Prize.

I recently learned some fascinating historical trivia.

Schrodinger was a neighbour of J.R.R. Tolkien, who during that time was finishing up work on The Hobbit.

It would be nice to see this landmark honoured, such as the one on Tolkien's house. However, it seems Schrodinger's house does not meet the criteria of Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Board, because he lived there for three years, less than the required minimum of five years.

Another option would be a plaque of the Institute of Physics, such as this one.

Tuesday, August 29, 2017

The most important concept in economics is emergence

This is not based on the hubris of a condensed matter physicist, but rather the claim of three economists in an Econtalk podcast, where Don Boudreaux, Michael Munger, and Russ Roberts discuss Emergent Order. For example, Boudreaux states

There is some disagreement between the three participants about whether the relevant terminology is "spontaneous order", "emergent order", or "self-organising system", but I did not find that particularly insightful.

One weakness of the discussion is that the three economists all have libertarian sympathies [i.e. they believe less regulation of markets the better] and there is an undercurrent in the discussion that this is justified by an emergent perspective. However, there are some really good comments on the podcast blog that eloquently argue against this and discuss the complexity of finding the right balance between free markets and government regulation. The comments are worth reading.

I thank my economist son for bringing the podcast to my attention and listening to it with me.

the notion of spontaneous order is indeed the most profound, single most profound insight of good economics. It remains the insight that is most elusive to the general public. Sadly, it remains an insight that is elusive to a lot of professional economists these days.The discussion centres around Robert's poem, "Its a wonderful loaf", the website for which has an animation of the poem and a nice list of related resources. The key idea is that free markets lead to an emergent order of prices, division of labour, and matching of supply and demand. This order is Adam Smith's "invisible hand" that guides the economy. It is actually "bottom up", not top down. Many of the ideas discussed are those originating with F. A. Hayek, in the context of not just economics but also in social and political philosophy. A summary I found helpful of Hayek's ideas is in a recent paper by Paul Lewis.

There is some disagreement between the three participants about whether the relevant terminology is "spontaneous order", "emergent order", or "self-organising system", but I did not find that particularly insightful.

One weakness of the discussion is that the three economists all have libertarian sympathies [i.e. they believe less regulation of markets the better] and there is an undercurrent in the discussion that this is justified by an emergent perspective. However, there are some really good comments on the podcast blog that eloquently argue against this and discuss the complexity of finding the right balance between free markets and government regulation. The comments are worth reading.

I thank my economist son for bringing the podcast to my attention and listening to it with me.

Tuesday, August 22, 2017

Managing my mental health

I have received positive feedback about previous posts about mental health and so I share some recent experiences in the hope it may be helpful to some.

I have had three significant times where my mental health deteriorated to the point I could not function “normally”. The first was during my Ph.D and the second about 15 years ago. The most recent experience was roughly six months ago. Here are a few things I learnt [or re-learnt] from this last experience.

The decline is often gradual and not perceived or denied.

It is like the proverbial frog in boiling water. It does not notice how the temperature is increasing and never jumps out.

The longer you wait to address the issue the slower the recovery.

Don't think things will get better on their own.

Mental illness is irrational.

That's the point. When I now think about some of the thoughts and perceptions that seemed “real” and “true” to me 6-12 months ago it is sad and bizarre.

Relapse is not uncommon.

If you have had previous incidents and recovered don't think it will never happen again.

Complexity.

There is high causal density. Diverse circumstances and stresses, whether work, family, social, or relational, may all contribute to varying degrees. Hence, the most effective solutions and treatments are likely to be multi-faceted.

Professional help.

Get it sooner than later.

Don’t self-diagnose.

Getting help also relieves the burden on family and friends.

Aside: In Australia (which is blessed with a reasonable national health scheme) a GP doctor can prescribe a mental health treatment plan which entitles the patient to subsidised sessions with a psychologist or psychiatrist.

[Mind you due to bureaucratic errors it took several phone calls and two visits to the Medicare office before the paperwork was actually processed properly…].

I went to see the same psychologist who I saw 15 years ago. This was helpful because she knew my history and issues. Also, I trusted her and knew she could help. I think one simple but significant value of these visits is the accountability to be making changes and addressing issues.

Medication.

It does not work for everyone. Some people have bad side effects.

There is a debate about whether antidepressants are over-prescribed. Medication should not be a substitute for talking therapies and lifestyle changes. However, medication sure works for me! After several years without, I went back on a small dose of an antidepressant. I still find it amazing the difference it makes. Just a little fine tuning of the brain chemistry....

Mindfulness.

Some of these meditation exercises may seem like New Age mumbo jumbo. However, when I did them 15 years ago, I learnt for the first time in my life to control my thoughts.

Again, going back to them really helped.

You will get better.

When you are physically ill, whether from flu or surgery, life can seem pretty bleak and it is hard to remember what normal was, and you may wonder whether you will ever get better. It is the same with mental illness. With appropriate treatment, healing usually does occur. But hope and patience are key.

Postscript (14 October).

Things are really getting better.

Thanks for the kind messages from people, including those who have shared some of their own stories.

It is encouraging that the President of University of British Columbia, Santa Ono, is speaking about his own struggles.

I have had three significant times where my mental health deteriorated to the point I could not function “normally”. The first was during my Ph.D and the second about 15 years ago. The most recent experience was roughly six months ago. Here are a few things I learnt [or re-learnt] from this last experience.

The decline is often gradual and not perceived or denied.

It is like the proverbial frog in boiling water. It does not notice how the temperature is increasing and never jumps out.

The longer you wait to address the issue the slower the recovery.

Don't think things will get better on their own.

Mental illness is irrational.

That's the point. When I now think about some of the thoughts and perceptions that seemed “real” and “true” to me 6-12 months ago it is sad and bizarre.

Relapse is not uncommon.

If you have had previous incidents and recovered don't think it will never happen again.

Complexity.

There is high causal density. Diverse circumstances and stresses, whether work, family, social, or relational, may all contribute to varying degrees. Hence, the most effective solutions and treatments are likely to be multi-faceted.

Professional help.

Get it sooner than later.

Don’t self-diagnose.

Getting help also relieves the burden on family and friends.

Aside: In Australia (which is blessed with a reasonable national health scheme) a GP doctor can prescribe a mental health treatment plan which entitles the patient to subsidised sessions with a psychologist or psychiatrist.

[Mind you due to bureaucratic errors it took several phone calls and two visits to the Medicare office before the paperwork was actually processed properly…].

I went to see the same psychologist who I saw 15 years ago. This was helpful because she knew my history and issues. Also, I trusted her and knew she could help. I think one simple but significant value of these visits is the accountability to be making changes and addressing issues.

Medication.

It does not work for everyone. Some people have bad side effects.

There is a debate about whether antidepressants are over-prescribed. Medication should not be a substitute for talking therapies and lifestyle changes. However, medication sure works for me! After several years without, I went back on a small dose of an antidepressant. I still find it amazing the difference it makes. Just a little fine tuning of the brain chemistry....

Mindfulness.

Some of these meditation exercises may seem like New Age mumbo jumbo. However, when I did them 15 years ago, I learnt for the first time in my life to control my thoughts.

Again, going back to them really helped.

You will get better.

When you are physically ill, whether from flu or surgery, life can seem pretty bleak and it is hard to remember what normal was, and you may wonder whether you will ever get better. It is the same with mental illness. With appropriate treatment, healing usually does occur. But hope and patience are key.

Postscript (14 October).

Things are really getting better.

Thanks for the kind messages from people, including those who have shared some of their own stories.

It is encouraging that the President of University of British Columbia, Santa Ono, is speaking about his own struggles.

Friday, August 18, 2017

From instrumentation to climate change advocacy

I learned a lot from reading In the Eye of the Storm: The Autobiography of Sir John Houghton (with Gill Tavner). He is arguably best known for being the lead editor of the first three reports of the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). He started his scientific life as an atmospheric physicist at Oxford. Here are a few things that struck me.

The value of development of new instruments.

At Oxford Houghton was largely involved in finding new ways to use rocket based instruments measure the temperature and composition of the atmosphere at different heights. These were crucial for getting accurate data that revealed the extent of climate change and understanding climate dynamics. It was good for me to read this. As a theorist, I am often skeptical or at least unappreciative of the value of developing new instruments. I think it is partly because I have heard too many talks about instrument design where it really wasn't clear they were going to generate useful and reliable information, particularly that could be connected to theory.

A reluctant administrator.

I think the best people for senior management are those who don't want the job. The worst are those who desperately want the job. It is interesting to see that Houghton was quite reluctant to leave Oxford when he was asked to be director of Rutherford-Appleton Lab. Then he wanted to go back to Oxford but was persuaded to become head of the Meteorological Office. It is also refreshing to see how he pushed back against some of the "management" nonsense that people wanted to impose on the organisations that he led.

Rigorous peer review at the IPCC.

Just because something is peer reviewed does not mean it is true. However, when there is an overwhelming consensus about some issue in peer-reviewed literature, we can high confidence it is true. Furthermore, at the IPCC there was really a double layer of peer review. The reports were based on reviews of the peer-reviewed literature. Every sentence in the reports was debated and ultimately voted on by a committee of leading scientists with relevant expertise. It is very hard to get scientists to agree on anything. However, when they can agree it means there must be a high probability it is true.

Dirty tactics of denialists.

There are a few stories about the different antics of "observers" at IPCC meetings who worked tirelessly to get IPCC to dilute their reports and sow doubt. Unfortunately, Federick Seitz features along with the lawyer/lobbyist Don Pearlman, who worked for the Global Climate Coalition.

Gracious public engagement.

The book describes how Houghton has worked hard to engage with climate change denialists, particularly among Conservative Christian leaders in the USA.

Finally, the book makes a strong case for concerted action on climate change. The most striking figure in the book was the map of Bangladesh showing how much will go under water, with just a one-metre rise in sea level. As often the case it is the poor that suffer the most.

The value of development of new instruments.

At Oxford Houghton was largely involved in finding new ways to use rocket based instruments measure the temperature and composition of the atmosphere at different heights. These were crucial for getting accurate data that revealed the extent of climate change and understanding climate dynamics. It was good for me to read this. As a theorist, I am often skeptical or at least unappreciative of the value of developing new instruments. I think it is partly because I have heard too many talks about instrument design where it really wasn't clear they were going to generate useful and reliable information, particularly that could be connected to theory.

A reluctant administrator.

I think the best people for senior management are those who don't want the job. The worst are those who desperately want the job. It is interesting to see that Houghton was quite reluctant to leave Oxford when he was asked to be director of Rutherford-Appleton Lab. Then he wanted to go back to Oxford but was persuaded to become head of the Meteorological Office. It is also refreshing to see how he pushed back against some of the "management" nonsense that people wanted to impose on the organisations that he led.

Rigorous peer review at the IPCC.

Just because something is peer reviewed does not mean it is true. However, when there is an overwhelming consensus about some issue in peer-reviewed literature, we can high confidence it is true. Furthermore, at the IPCC there was really a double layer of peer review. The reports were based on reviews of the peer-reviewed literature. Every sentence in the reports was debated and ultimately voted on by a committee of leading scientists with relevant expertise. It is very hard to get scientists to agree on anything. However, when they can agree it means there must be a high probability it is true.

Dirty tactics of denialists.

There are a few stories about the different antics of "observers" at IPCC meetings who worked tirelessly to get IPCC to dilute their reports and sow doubt. Unfortunately, Federick Seitz features along with the lawyer/lobbyist Don Pearlman, who worked for the Global Climate Coalition.

Gracious public engagement.

The book describes how Houghton has worked hard to engage with climate change denialists, particularly among Conservative Christian leaders in the USA.

Finally, the book makes a strong case for concerted action on climate change. The most striking figure in the book was the map of Bangladesh showing how much will go under water, with just a one-metre rise in sea level. As often the case it is the poor that suffer the most.

Wednesday, August 9, 2017

Subtle paths to effective Hamiltonians in complex materials

Many of the most interesting materials involve significant chemical and structural complexity. Indeed, it is not unusual for a unit cell for a crystal to contain the order of one hundred atoms.

Yet, for a given class of materials, one would like to find an effective Hamiltonian involving as few degrees of freedom and parameters as possible.

Following Kino and Fukuyama, twenty years ago I argued that the simplest possible effective Hamiltonian for a large class of superconducting organic charge transfer salts was a one-band Hubbard model on an anisotropic triangular lattice at half filling.

It seemed natural to then argue that the relevant model for the spin degrees of freedom in the Mott insulating phase is the corresponding frustrated Heisenberg model with spatial anisotropy determined by the anisotropy in the tight-binding model.

However, it turns out this is not the case.

There are some subtle quantum interference effects that I overlooked in the "derivation" of these effective models, leading to a different spatial anisotropy.

This is shown by some of my colleagues in a nice recent paper, accepted for PRL.

Dynamical reduction of the dimensionality of exchange interactions and the "spin-liquid" phase of κ-(BEDT-TTF)2X

B. J. Powell, E. P. Kenny, J. Merino

This raises questions about what the relevant effective Hamiltonian is for the metallic, superconducting, and (possibly) ferroelectric phases.