Science education in schools in the Majority World faces many challenges including lack of resources, poorly trained teachers, and a fixation on rote learning from textbooks. Even at “good” schools students rarely ever do experiments or hands-on demonstrations. The focus is on preparing standard answers for exam questions.

One recent big change in school education in the Majority World is the proliferation of low-cost private schools, even in extremely poor communities. Most of these are English medium. A recent cover story in The Economist chronicled this development.

When visiting India, I enjoy reading The Hindu newspaper each day. I think the quality of journalism and the substance of the issues covered is much higher than most Western newspapers. More than once a week there is an op-ed piece or article about the problems with school education. Topics covered include the stifling of critical and creative thinking, the lack of autonomy given to teachers by all-knowing and controlling principals, …

Here is roughly what I have done for the science lesson in a school in the Majority World.

The main goal is to give a hands-on experience that will help the students see that what they read in the textbook or memorise for the exam actually has something to do with the real world.

It is centred around a baking soda and vinegar film canister rocket. Since this involves cheap household chemicals the hope is the children and/or their teachers might do it again.

I begin with a brief discussion of the scientific "method": ask a question, make a hypothesis (a big idea), design an experiment, make measurements, record data, analysis data, conclusion, and communicate results. I then illustrate this by sticking a wooden skewer in a balloon then show how you can actually put the skewer through the balloon.

I do the film canister rocket experiment. I then just mix a little vinegar and baking soda so they can see gas is being produced. Why is there gas? What gas is it?

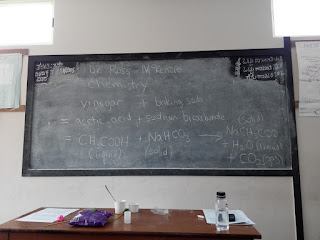

I then explain what chemistry is and illustrate with the chemical reaction of baking soda and vinegar, using full chemical names and chemical formula. Since carbon dioxide is a product we briefly discuss global warming. I highlight that different compounds in the chemical reaction are gas, solid, or liquid.

I then turn to physics. There are two relevant ideas here:

1. Newton's third law [which they all know word perfect!] and that drives the rocket.

2. When you convert a fixed mass of liquid or solid to gas the total volume increases by a thousandfold. A few grams of carbon dioxide has a volume of several hundred millilitres. Compressing that into the film canister produces a huge pressure.

Now the fun and most important part. We go outside and the students work in pairs where they systematically vary the amount of vinegar they add to the film canister and measure (estimate) the height the rocket goes to. Does more vinegar increase or decrease the height? Why or why not? They record their results. The quicker students I get to repeat their measurements.

After a lot of fun, we return to the classroom. I review the chemistry and physics again. Then we compare measurements between different groups, discuss measurement error, and try and draw some conclusions.

The second week I was really happy because a local friend came who just finished a Ph.D. He came from a similar socio-economic background to many of the students. I asked him to tell his life story to the class in the hope it would inspire the students. I don't think a wealthy white Western guy telling poor kids they should study hard and have a lofty goal such as to become a scientist is particularly effective or appropriate.

Follow up. The following week I did the same session with three high school students who were being home schooled by their parents. I was very impressed by their creativity and critical thinking. On their own initiative, they realised that it was difficult to make accurate measurements of the height that the rocket went to. Their solution was within about ten minutes to construct the launch device below. Instead of measuring the vertical distance they used a tape measure to measure the horizontal distance the rocket travelled.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Information theoretic measures for emergence and causality

The relationship between emergence and causation is contentious, with a long history. Most discussions are qualitative. Presented with a new...

-

This week Nobel Prizes will be announced. I have not done predictions since 2020 . This is a fun exercise. It is also good to reflect on w...

-

Is it something to do with breakdown of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation? In molecular spectroscopy you occasionally hear this term thro...

-

Nitrogen fluoride (NF) seems like a very simple molecule and you would think it would very well understood, particularly as it is small enou...

No comments:

Post a Comment