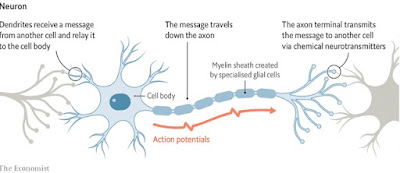

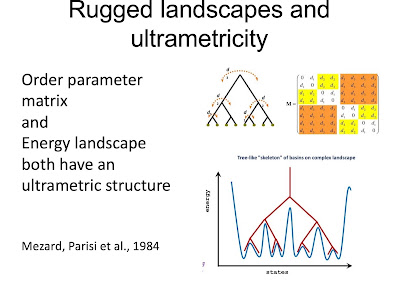

Any organisation is composed of many interacting parts. For example, a university is not just composed of staff and students, but also includes collaborators, donors, employers, suppliers, parents, graduates, and trustees. Their interactions with one another are influenced by structures, such as buildings, committees, and government policy. Furthermore, a university exists in a context: political, economic, historical, and cultural. What emerges from the interactions of all these components may be new states, for good or for ill. Like all emergent phenomena these states are hard to predict. For example, what will lead to high-quality education or a diverse student body? Can desirable outcomes be managed? What is the role of leadership in large organisations? Are there some universal principles of management that are useful for a wide range of organisations, whether corporations, NGOs, universities, or government departments?

Researching, teaching, and writing about "Organisational Development" and "management" is a massive industry; from Business schools in universities to a multitude of popular books for sale in airports. A fascinating paper is

The Dialogic Mindset: Leading Emergent Change in a Complex World by Gervase Bushe and Robert Marshak.

It questions the paradigm of the "visionary leader", "command and control", and the "performance mindset" that focuses on instrumental and measurable goal setting and achievement.

To understand the limitations of this management paradigm I find it helpful to reflect on the history and context of how it emerged (!) in the USA after World War II. After the war, veterans who returned to civilian life had experienced a particular leadership and organisational culture of the military: hierarchy, authority, process, discipline, solidarity, male, mono-cultural, ... And, it worked in the context of war!

Many war veterans, both junior and senior, took this approach and mentality into industry, and it worked well in the American post-war economic boom of assembly-line-based large-scale manufacturing. The automotive industry, centred around Detroit, was representative. Arguably, the success was based on efficiency not innovation, limited competition in a simple market, and a homogeneous workforce. Two important figures who emerged from this Detroit era were Peter Drucker and Robert McNamara. Drucker did a seminal two-year study of General Motors, during WWII, that started his trajectory towards becoming the doyen of management studies. McNamara took his strategic planning experience in the war, and applied it successfully at Ford for 15 years, rising to become President of Ford in 1960. He then became Secretary of Defense for JFK and used the same management approach for the USA's involvement in the Vietnam war. This was an unmitigated disaster, but that did not stop him from using a similar approach when President of the World Bank.

Back to Bushe and Marshak and today's world. They claim that

The “visionary leader” narrative and performance

mindset that predominate in theories and practices

of “Change Leadership” are no longer effective

in an environment of multi-dimensional diversity

marked by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and

ambiguity.

The prevailing narrative of leadership is based on the assumption that great leaders must [be strategic thinkers], have a vision, and the ability to lead followers to that vision. Leaders, followers, and commentators alike assume that being a visionary is indispensable to organizational leadership.

... a leading voice supporting an alternative paradigm is Heifetz’s (1998) leadership model that indirectly challenges the heroic, visionary orthodoxy. He divides the decision situations leaders face into technical problems, which can be defined and solved through a top-down imposition of technical rationality; and adaptive challenges, which can only be “solved” through the voluntary engagement of the people who will have to change what they do and how they think.

In Heifetz’s alternative narrative of leadership, adaptive leaders identify challenges but instead of providing solutions, they encourage employees and

other stakeholders to propose and act on their own

solutions.

A nice example is how employees shaped strategy at the New York Public Library.

The problem with the standard narrative is that it overlooks that organisations are emergent entities where cause-effect relations are not understood and outcomes are hard to predict. This challenge is exacerbated today by the fact that any organisation is not an isolated entity but is immersed in a complex and rapidly changing environment. This puts a premium on innovation and adaptability.

Future posts will explore what this might mean in practice. Can self-organising processes and emergence achieve desired outcomes by "changing the conversation"?